The Birth of Nations: SCOTLAND

the Lie of the Land

In the 6th century the country now called Scotland was divided amongst three different ‘peoples’: Britons, Picts and Scots.

To the south of the Forth-Clyde isthmus were P-Celtic speaking Britons.[*] In the east, the territories of the tribe known to the Romans as the Votadini had metamorphosed into the kingdom of Gododdin.

(Dál Riata)

clyde)

There was a kingdom based at Alt Clut (Rock of the Clyde) – Dumbarton Rock on the north shore of the Clyde. The stronghold at Dumbarton was devastated by Vikings in 870, after which the kingdom becomes known as Strat Clut (Valley of the Clyde), i.e. Strathclyde. Although it may not reflect contemporary usage, the name Strathclyde is generally also used for the king of Alt Clut’s territory. Between this embryonic Strathclyde and the Solway Firth, other kingdoms are hinted at in various sources, but have no known history – for instance Goddau, mentioned in Welsh poetry attributed to the 6th century bard Taliesin.[*] Taliesin is particularly associated with Rheged – a kingdom that may have held lands north and south of the Solway Firth (which now forms the western end of the English-Scottish border).[*][*]

Most of the country north of the Forth-Clyde was occupied by the Picts (who probably spoke a P-Celtic language, though this remains a subject of debate), but in Argyll, on the west coast, the Q-Celtic speaking Scots had established the kingdom of Dál Riata (Dalriada).[*]

The Picts remain an enigmatic people. According to a fable, which seems to have Irish origins, the eponymous founding father of the Picts was Cruithne (Cruithni being the Irish name for the Picts).[*] He had seven sons: Fib, Fidach, Floclaid, Fortrenn, Got, Ce, Circinn (the spellings vary – these are from the Pictish king-list in the Poppleton Manuscript). The brothers divided their father’s country, and their provinces were named after them. This is typical foundation-myth stuff, but the divisions are apparently real enough – Got (elsewhere: Cait) equates to Caithness and Fib to Fife; Fortrenn is the Irish genitive of Fortriu, which corresponds to the name of a Pictish tribe known to 4th century Romans, the Verturiones[*].

A confused and contradictory 12th century geographical tract, De Situ Albanie (On the Situation of Alba), found in the Poppleton Manuscript, says that Alba (meaning Britain north of the Forth-Clyde isthmus[*]) was, in ancient times, divided amongst seven brothers. It names the regions they ruled, in 12th century terms, but only names one of the brothers: Oengus (in modern parlance, Angus), after whom “Angus with Mearns” was named.[*] De Situ Albanie then proceeds to muddy the water by describing the seven kingdoms again, quoting rather vague geographical boundaries, and producing a list of regions which does not correlate with the first list.[*] At any rate, on the basis that they genuinely represent an early state of Pictish political affairs, scholars have attempted to match the clearly named regions, from the first list in De Situ Albanie, to the seven sons of Cruithne: “Angus with Mearns” matched to Circinn; “Atholl and Gowrie” to Floclaid; “Strathearn with Menteith” to Fortrenn (i.e. Fortriu); “Fife with Fothriff” to Fib; “Mar with Buchan” to Ce; “Moray and Ross” to Fidach; “Caithness on this side of the mountain, and beyond the mountain” to Got. These identifications are, however, of varying degrees of certainty: whilst Fib = Fife + Fothriff, and Got = Caithness [+ Sutherland] seem reasonable equations, Fidach = Moray + Ross is arrived at simply by process of elimination.[*]

On firmer ground, the renowned Anglo-Saxon scholar Bede says (HE III, 4) that the Picts were divided into two groups – the northern and the southern – separated “by steep and rugged mountains”. This mountainous divide was called ‘the Mounth’ (Grampians).[Map] Bede proceeds to imply that in the year 565, Bridei son of Maelchon, “the powerful king”, was ruling over all the Picts – i.e. over both the northern and the southern groupings. Later (HE V, 21), Bede clearly presents King Nechtan (son of Derelei) as, around the year 710, having authority over “all the provinces of the Picts”. Both of these rulers appear in Pictish king lists, which show just one line of succession – presumably over-kings of the whole Pictish nation. By the time of Bridei son of Beli (Bridei famously defeated the Northumbrian English in 685), it seems that Fortriu was the dominant Pictish kingdom, and their kings were over-kings of the Picts.

Bede notes (HE I, 1) that “when any question should arise” the Picts chose “a king from the female royal race rather than from the male”. Actually, in Pictish king lists there isn’t even the possibility of a king being the son of a previous king until the 780s. Indeed, some kings of the Picts appear to have had non Pictish fathers. Two that can be identified with some certainty are Talorcan (r.653–657) and Bridei (r.672–693). Talorcan’s father was the Anglo-Saxon Eanfrith, who, briefly (around 633), was king of Bernicia. Bridei’s father was Beli, king of the Strathclyde Britons. Some scholars have concluded that matrilineal succession (i.e. via the female line) was the norm with the Picts, and not just “when any question should arise”.[*]

In Bede’s day, there were, he reports, five languages in use in Britain:

… to wit, English, British [P-Celtic], Scottish [i.e. Irish, Q-Celtic],[*] Pictish, and Latin, the last having become common to all by the study of the Scriptures.HE I, 1

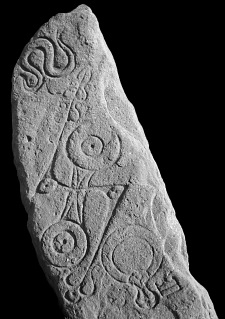

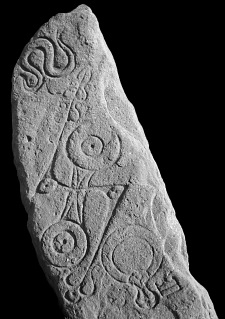

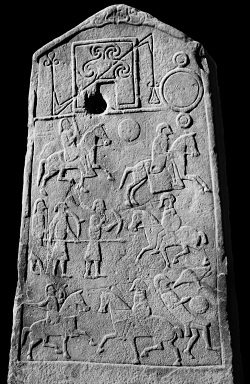

What type of language the Picts spoke has (like every other facet of Pictish history) long been the subject of scholarly conjecture. There is little information to go on – mainly place-names and personal-names, but there are also inscriptions. The Picts have left a legacy of elaborately carved standing-stones, some apparently engraved with ogham inscriptions – ogham being a writing-system, where a character is defined by the number and orientation of straight strokes relative to a stem-line, which seems to have originated in Ireland in the 4th century. St Columba’s biographer, Adomnán, says (VC II, 32) that Columba, an Irishman, needed an interpreter to preach to the Picts, and the Pictish inscriptions have defied satisfactory translation.[*] To cut a very long story short, the majority view seems to be that the Picts spoke a P-Celtic language. The intractability of what appears to be ogham writing on stones has, however, encouraged the notion that they are in a pre-Celtic remnant language (similar to Basque). It is not only the ogham aspect of Pictish carved stones which has been the subject of scrutiny. There is repeated use of certain designs, known as ‘Pictish symbols’, which it is believed must have meaning, but what that meaning is has, so far, also resisted would-be code-breakers.

The 2nd century geographer Ptolemy, working from 1st century materials, placed a tribe called the Epidii in the region that became Dál Riata.[*] Presumably the Epidii would have been regarded as Picts when that term came into use in the 3rd century.[*] So how and when did the Scottish, i.e. Irish, kingdom of Dál Riata become established on British soil? According to a tradition known to Bede:

In process of time, Britain, besides the Britons and the Picts, received a third nation, the Scots, who, migrating from Ireland under their leader, Reuda, either by fair means, or by force of arms, secured to themselves those settlements among the Picts which they still possess. From the name of their commander, they are to this day called Dalreudini; for, in their language, Dal signifies a part.HE I, 1

Bede’s ‘Reuda’ would seem to be the equivalent of Coirpre Riata (Rigfota), who, in two manuscripts, features in the Preface to the Irish poem Amra Choluim Chille. According to this story, Coirpre Riata’s “race” were forced, by a famine, to leave their Munster (south-west Ireland) homeland: “and the one part of them went into Alba, and the other part remained in Ireland, and thence are the [men of] Dál Riata today.” Dál Riata did indeed straddle the North Channel – comprising territory in Antrim, on the east coast of northern Ireland, as well as in Argyll, on the west coast of what would become Scotland. The pedigree of Mael Coluim son of Cinaed, conventionally designated Malcolm II of Scotland, who reigned 1005–1034, appearing (¶1696) amongst a collection of genealogies in a 12th century Irish manuscript (Oxford, Bodleian MS Rawlinson B 502), places one Fergus son of Erc seventeen generations after Coirpre Riata.[*] The Scottish king-list in the Poppleton Manuscript begins with the announcement that, not Coirpre Riata, but:

Fergus son of Erc, was the first of Conaire’s race to receive the kingdom of Alba; that is, from the mountain of Drumalban as far as to the sea of Ireland, and to the Hebrides. He reigned for 3 years.

An entry (evidently not written before the 10th century[*]) in the Annals of Tigernach states that, c.500: “Fergus Mór son of Erc, with the people of Dál Riata, held a part of Britain, and there he died.” By these tokens (allowing around twenty years per generation), the Reuda/Coirpre Riata character would belong in the 2nd century.

Fergus is purported to have crossed over from Ireland with his brothers.[*] The eighth verse (of twenty-seven) of a late-11th century Irish poem, the Duan Albanach, runs:

The three sons of Erc son of pleasant Eochaid,

three who got the blessing of Patrick [d.c.493?],

took Alba, high was their vigour,

Loarn, Fergus, and Oengus.

From this point, the Duan is simply a versified list of Scottish kings, concluding during the reign of Malcolm III (1058–1093). In the next verse (i.e. the ninth), Loarn is said to have ruled for ten years, after which Fergus is said to have ruled for twenty-seven years. Another source, evidently derived from the same lost king-list as the Duan, the Synchronisms traditionally attributed to Irish scholar Flann Mainistrech (who died in 1056, but no manuscript of the Synchronisms is earlier than the 14th century), however, gives no reign to Loarn, but gives Oengus a reign after Fergus (reign lengths are not provided in the Synchronisms). Nowhere else are Loarn or Oengus considered to have had the overall rule of Dál Riata.[*]

The Senchus fer nAlban (History of the Men of Alba), which apparently has 7th century origins, but also 10th century modifications, reports that the territory of British Dál Riata was divided between three main kin-groups (cenéla), each named from the group’s founding father.[Map] In the mid-9th century, the Scots of British Dál Riata and the Picts were finally united under a single king. By 900, the unified kingdom was called Alba (which came to be called, in English, Scotland). The kin-group from which the kings of Alba claimed descent was the Cenél nGabráin – who, according to the Senchus fer nAlban, originally held the territory of Kintyre and Cowal “with its islands” – named after Gabrán, who is presented as Fergus Mór’s grandson. The founders of the other two groups, the Cenél nOengusa, who occupied Islay, and the Cenél Loairn, who, by implication, occupied Lorn, are presented as Fergus’ brothers, Oengus Mór and Loarn Mór. The Senchus is the earliest source to portray Loarn and Oengus as Fergus’ brothers. They probably weren’t – it is likely they were incorporated into the mythology of the kingdom of Alba in the 10th century. James VI of Scotland, who also became James I of England in 1603, describes himself (in the sonnet ‘To the Queene, Anonimos’) as: “happie monarch sprung of Ferguse race”. Fergus himself, though, could also be a 10th century fabrication (it is telling that there was no kin-group named from him). Some scholars go further – suggesting that the whole notion of Dál Riata being established in Britain by Irish trespassers is itself a fabrication.

There must have been traffic between Antrim and Argyll since time immemorial – they are separated by only a dozen miles of sea – but there is no archaeological evidence to suggest that large numbers of people migrated from Ireland to Argyll, nor even that there was a takeover of the native population by an Irish elite. There is no doubt, however, that the Dál Riatans spoke the same language as the Irish (Q-Celtic). Archaeologist Ewan Campbell, in an article titled ‘Were the Scots Irish?’,[*] argues that the short sea passage between Argyll and Antrim was much less of a barrier to communications than the mountains of the Highlands, and, as a consequence, the natives of Argyll, Ptolemy’s Epidii, were Q-Celtic speakers. “By the early medieval period,” writes Dr Campbell, “the emphasis on marine transport in Argyll allowed the development of a formidable navy, capable of maintaining a strong political identity within Argyll, and allowing Dál Riata to become an expansionist force in the area attacking as far away as Orkney, the Isle of Man and the west coast of Ireland [as will be seen later]. For a time during this early period, Dál Riata extended its control to the area of Antrim closest to Argyll … and this area also became known as Dál Riata. During the Middle Irish period, when claims of the Irish ancestry of Scottish royalty were being elaborated, a process of ‘reverse engineering’ was used by Irish writers to explain the existence of an Irish Dál Riata as the progenitor of Scottish Dál Riata rather than vice versa.” Be all that as it may, Fergus son of Erc is said (except in the Synchronisms) to have been succeeded by his son, Domangart.

the 6th Century

Domangart son to noble Fergus,

the number of five ever-fierce years;

24 without strife

for Comgall son of Domangart.

So says the Duan Albanach (Verse 10). The figure of Domangart seems to act as the interface between the fabricated backstory and Scottish history proper. The Annals of Ulster (AU), in a somewhat garbled entry, that begins “as some say”, place Domangart’s death, or perhaps his retirement into religion, in 507.[*] Domangart’s successor was his son, Comgall, whose death, “in the 35th year of his reign”, is placed s.a. 538 by AU; then again, without reign length, in 542; and yet again, “as some say”, in 545. Comgall was succeeded by his brother, Gabrán. The announcement of Gabrán’s death appears in both 558 and 560. His successor was his nephew (Comgall’s son), Conall.

In the same year as Gabrán’s death, though not necessarily associated with it, Dál Riatan expansion appears to have suffered a setback, at the hands of the Pictish king, Bridei son of Maelchon. AU also records this event in both 558 and 560. The earlier of the two entries is in Latin, and it refers to the “flight before Maelchon’s son”, whereas the later entry is in Irish, and it reports the “migration before Maelchon’s son”. The notion of migration does tend to imply that the Picts had forced the Scots to abandon territory they had previously occupied.

AU places the “voyage of Colum Cille to the island of Iona” in 563. Colum Cille, literally ‘dove of the church’, was an Irish missionary, and he is probably more familiar as St Columba. Bede, who places Columba’s voyage in 565, reports that:

… there came into Britain from Ireland a priest and abbot, a true monk in life no less than habit, whose name was Columba, to preach the word of God to the provinces of the northern Picts, who are separated from the southern parts belonging to that nation by steep and rugged mountains.[Map] For the southern Picts, who dwell on this side of those mountains, had, it is said, long before forsaken the errors of idolatry, and received the true faith by the preaching of Bishop Ninian, a most reverend and holy man of the British nation, who had been regularly instructed at Rome in the faith and mysteries of the truth[*] … Columba came into Britain in the ninth year of the reign of Bridei, who was the son of Maelchon, and the powerful king of the Pictish nation, and he converted that nation to the faith of Christ, by his preaching and example. Wherefore he also received of them the gift of the aforesaid island [Iona] whereon to found a monastery.[Map]HE III, 4

Although Bede says it was the Picts who gave Iona to Columba, Irish annals (e.g. AU, s.a. 574) say that it was Conall son of Comgall, king of Dál Riata, who made the gift. It may be that Columba prudently secured permission to settle on Iona from both the Picts and the Scots – it is not possible to be certain just who would have held sovereignty over Iona in 563. At any rate, Columba’s biographer, Adomnán (d.704), the ninth abbot of Iona, relates that:

… at the time when the Saint [Columba] was weary from his first journey to King Bridei, it so happened that that king, elated by royal pride in his fortress, acting haughtily, did not open the gates at the blessed man’s first arrival. [Adomnán places Bridei’s fortress in the vicinity of the river Ness – it is widely identified with the hillfort at Craig Phádraig.[*]] And when the man of God knew this, he came with his companions to the wickets of the portals, and first traced on them the Sign of the Lord’s Cross and then knocking, he lays his hand against the doors, and immediately the bolts are violently shot back, the doors open in all haste of their own accord, and being thus opened the Saint thereupon enters with his companions. Upon this being known the king with his council is greatly affrighted, and issues forth from his house to meet the blessed man with all reverence, and addresses him gently with conciliatory words. And from that day forth this ruler honoured the holy and venerable man with very great honour all the remaining days of his life; as was proper.VC II, 35

Adomnán does not, however, say that Bridei adopted Christianity.

Columba is said, by Adomnán (VC I, 15), to have been a friend of “King Rhydderch, son of Tudwal, who reigned upon the Rock of the Clyde.” ‘The Rock of the Clyde’ (Petra Cloithe, a Latinization of the P-Celtic Alt Clut) is Dumbarton Rock on the north shore of the Clyde. It was the royal seat of the British kingdom of Strathclyde (though the name ‘Strathclyde’ does not itself appear until the 9th century). Adomnán says that Rhydderch sent a messenger on a secret mission to Columba, to ask the saint: “whether he was to be slain by his enemies or not.” Columba replied:

“Never will he be delivered into his enemies’ hands, but in his own house will he die upon a feather bed.” Which prophecy of the Saint concerning King Rhydderch was fully accomplished, for, according to his word, he did die a peaceful death in his own house.VC I, 15

Indeed, in some Welsh texts Rhydderch ap Tudwal is given the epithet ‘Hen’ (the Old). The earliest Welsh collection of royal genealogies, contained in Harleian MS 3859 (although the manuscript itself dates from c.1100, the genealogies were probably collected in the later-10th century), presents (§6) Rhydderch Hen as the great-grandson of Dyfnwal Hen, who is, in turn, presented (§5) as the grandson of one Ceretic Guletic. This Ceretic is widely equated to the Coroticus who is featured in a letter written by St Patrick himself, and is also mentioned by Patrick’s biographer, Muirchu (late-7th century):

… a certain British king called Coroticus, an ill-starred and cruel tyrant. He was a very great persecutor and murderer of Christians.Vita Sancti Patricii §29

Returning to the supposed great-great-great-grandson of Coroticus; Rhydderch Hen is, in the Historia Brittonum (§63), associated with three other North British kings campaigning against Anglo-Saxon Bernicia[*]. In a Welsh Triad (No. 2), Rhydderch ap Tudwal is one of the “Three Generous Men of the Island of Britain”, and it is as Rhydderch Hael (the Generous) that he is usually known.[*] It is, though, without any epithet that Rhydderch appears as the patron of St Kentigern in a 12th century ‘Life’ of this obscure North-British saint[*].

The Annals of Ulster (AU) record the death, “in the 16th year of his reign”, of Conall son of Comgall, king of Dál Riata, s.a. 574. Conall was succeeded by Aedán, a son of, his predecessor and uncle, Gabrán.

In the following year, that is s.a. 575, AU places: “The great convention of Druim Cett” – referred to by Adomnán (VC I, 49) as “the convention of the kings”. There were two kings present at Druim Cett (which is identified as the Mullagh, also known as Daisy Hill, near Limavady, County Londonderry), Aedán of Dál Riata, who had travelled to the meeting with Columba, and Aed son of Ainmire, a king of the Northern Uí Néill dynasty (who ruled north-western Ireland) and kinsman of Columba. The Preface to the Amra Choluim Chille preserves some detail of the proceedings. One of the items on the agenda was: “to make peace between the men of Ireland and of Alba [i.e. the Scots of Britain] regarding Dál Riata.”[*] Although Dál Riata was based in Argyll, it still retained its territory in Antrim, on the north-eastern coast of Ireland, and it appears that it was the Irish Dál Riatans who were the point at issue. The outcome of the talks seems to have been that, although they would pay their dues to Aedán, and his successors, in Argyll, their military service would be paid to Aed, and his successors, in Ireland.

The only date for Druim Cett is the one provided by AU, i.e. 575, but it is problematic. Until after the death of his kinsman, Baetán son of Ninnid, which AU places in 586, Aed son of Ainmire does not seem to have been a king – by which token it would appear that the notice of Druim Cett has been inserted more than a decade too early.[*] At the time Aedán succeeded to the throne of Dál Riata, the dynamic force in the North of Ireland was apparently Baetán son of Cairell, king of the Ulaid (from which the name of Ulster derives). According to an Irish tract in the late-12th century Book of Leinster: “Baetán son of Cairell was king of Ireland and Alba. Aedán son of Gabrán submitted himself to him at Ros-na-Rig in Semniu [Island Magee, near Larne, Antrim].”

AU dates a battle, at an unlocated site (“the battle of Teloch”) in Kintyre, to 576 (and mentions it again in 577): “In which fell Dúnchadh son of Conall son of Comgall and many others of the followers of Gabrán’s sons fell.”[*] The annal’s phraseology and the place of the battle could indicate it was an internal dispute. Indeed, given the chronological confusion evident in the annals around this time, it may be that there was a war of succession following Conall’s death, and the battle in Kintyre was the decisive engagement that secured the throne for Aedán. Another possibility is that this attack, mounted from Ireland, compelled Aedán to submit to Baetán son of Cairell.

Aedán seems to feature in a cryptic Irish poem known as the Prophecy of Berchán (the relevant part was apparently composed in the late-11th century), which claims that he was at war with the Picts for thirteen years.[*]

Adomnán tells how Columba met with Bridei (son of Maelchon), king of the Picts:

… in the presence of the under-king of the Orkneys, saying: “Some of our people [i.e. Christian monks] have lately gone forth hoping to find a solitude in the pathless sea, and if perchance after long wanderings they should come to the Orkney islands, do thou [Bridei] earnestly commend them to this under-king, whose hostages are in thy hand, that no misfortune befall them within his territories.”VC II, 42

The Orkneys were clearly under Bridei’s control, but AU, s.a. 580 states: “The expedition to the Orkneys by Aedán son of Gabrán.” (And the next year, 581, repeats: “The expedition to the Orkneys.”) Though the annal is typically short on detail, this was certainly no holiday cruise. A Welsh Triad (No. 29), ‘Three Faithful War-Bands of the Island of Britain’, places in second place: “the War-Band of Gafran son of Aeddan [presumably, Aedán son of Gabrán is meant], who went to sea for their lord”.

An entry s.a. 582 in AU says that Aedán was victorious in “the battle of Manu”. Aedán’s victory in this battle is repeated s.a. 583.[*] Manu (genitive: Manann), in Irish, could be the Isle of Man, or the region around-about Falkirk, called Manaw in Welsh.

Adomnán reports (VC I, 8–9) that, at an unspecified date, Aedán, though victorious, suffered heavy losses – “three hundred and three men”, amongst whom were two of his sons, Artur and Eochaid Find – at “the battle of the Miathi”. The Miathi, whom Adomnán calls “barbarians”, probably correspond to the Maeatae, a people mentioned in connection with the Roman emperor Septimius Severus during the period 197–211[*]. It is widely held that the name of Dumyat, a hill with a hillfort, less than four miles to the north-east of Stirling, derives from ‘Dun [fortress] of the Maeatae’. Myot Hill, site of another hillfort, some seven miles north-west of Falkirk, may also preserve the name of the Maeatae. The territory suggested by these locations would appear to border, perhaps overlap, Manaw. Maybe, then, Adomnán’s “battle of the Miathi” is the Irish annals’ “battle of Manu”. Possibly, though, it is more likely that in this instance Manu means the Isle of Man.

There is mention, placed s.a. 577 by AU, of: “The first expedition of the Ulaid to Man [Eufania].” Then, s.a. 578: “The return of the Ulaid from Man [Eumania].” The implication is that the Ulaid mounted further, unrecorded, campaigns in the Isle of Man. According to the tract on Baetán son of Cairell, king of the Ulaid, in the Book of Leinster: “it was by him that Manu was cleared; and the second year after his death the Irish abandoned Manu.” It seems plain that, by Manu, the Isle of Man is meant. Baetán’s death is placed in 581 (and again, with the comment “or here”, in 587) by AU. Aedán’s victory at the “battle of Manu” is placed in 582 and 583. The Annales Cambriae, indicating a date of 584, report: “Battle against Man [Eubonia]”. It doesn’t seem unreasonable to equate this battle “against Man” with the “battle of Manu”. Perhaps, as a result of Aedán’s victory, the Ulaid “abandoned Manu” and the island became, for the time being, a Dál Riatan possession – Bede asserts that, the Northumbrian king, Edwin, who ruled from 616 to 633, brought the Isle of Man “under the dominion of the English”.[*]

The death of Bridei son of Maelchon, king of the Picts, is placed s.a. 584 by AU.[*] However, the Pictish king-list in the Poppleton Manuscript grants him a reign of 30 years, and Bede (HE III, 4) equates his ninth year to 565, by which tokens his thirtieth year would have been 586.

In 590 Aedán apparently defeated an unnamed foe at the, unlocated, “battle of Leithreid” (AU), whilst, according to a Welsh Triad (No. 54), the third of the ‘Three Unrestrained Ravagings of the Island of Britain’ was: “when Aeddan Fradog [the Wily] came to the court of Rhydderch Hael [the Generous] at Alt Clut; he left neither food nor drink nor beast alive.”

Rhydderch Hael, i.e. Rhydderch ap Tudwal, ruled the Strathclyde Britons from the stronghold of Alt Clut (Dumbarton Rock). According to Adomnán (VC I, 15) he was a friend of Columba, and he died: “a peaceful death in his own house.” The date of Rhydderch’s death is nowhere directly recorded, but a late-12th century Vita of St Kentigern has it that he died in the same year as Kentigern, which event the Annales Cambriae place c.612.[*]

Adomnán says that Columba died on Iona 34 years after his first arrival on British shores. AU, which should, therefore, place Columba’s obit in 597, actually places it in 595: “Repose of Colum Cille on the 5th of the Ides of June [9th of June] in the 76th year of his age.”[*] Assigned to the year following Columba’s death (so, though appearing s.a. 596, it might well belong to 598) is: “The slaying of Aedán’s sons, i.e. Bran and Domangart.” Adomnán doesn’t mention Bran, but says (VC I, 9) “Domangart was killed in Saxonia [i.e. Northumbria], in the bloodshed of battle”.

the 7th Century

Attributed to the bard Aneirin is Y Gododdin, a long elegiac Welsh poem which records the defeat of an elite band of warriors – there were three hundred of them – who had ridden from the British kingdom of Gododdin to engage Northumbrian forces at Catraeth (usually, though without certainty, identified as Catterick). The Britons, led by one Mynyddog Mwynfawr (Mynyddog the Wealthy), were annihilated by the vastly greater number of Englishmen. The battle of Catraeth, assuming it really happened, is generally dated c.600 – early in the reign of the Northumbrian king, Æthelfrith (though he is not named in the poem). Bede reports that Æthelfrith:

… conquered more territories from the Britons than any other chieftain or king, either subduing the inhabitants and making them tributary, or driving them out and planting the English in their places… Aedán, king of the Scots that dwell in Britain, being alarmed by his success, came against him with a great and mighty army, but was defeated and fled with a few followers; for almost all his army was cut to pieces at a famous place, called Degsastan, that is, Degsa Stone [not certainly identified]. In which battle also Theobald, brother to Æthelfrith, was killed, with almost all the forces he commanded. This war Æthelfrith brought to an end in the year of our Lord 603 … From that time, no king of the Scots in Britain has dared to make war on the English to this day.HE I, 34

AU assigns Aedán’s death to 606. There is not complete agreement in the number of years reign granted him by various king-lists and annals, but allowing for typical scribal errors in the transmission of Roman numerals, the underlying figure seems to be 34 years. It would appear that AU has, once more, placed the event too early, and Aedáns death should be in 608. However, the Prophecy of Berchán, assuming it really does preserve material relevant to Aedán, says that he was no longer king at the time of his death, which occurred on a Thursday, in Kintyre. Moreover, the early-9th century Martyrology of Tallaght (that survives in a 12th century manuscript that was once part of the Book of Leinster) lists Aedán (Aedhani Mac Garbain) among those worthies who died on the 17th of April – which fell on a Thursday in 609. According to AT, Aedán was in his 74th year when he died.[*] As purportedly predicted by Columba, he was succeeded by his son, Eochaid Buide.[*]

In 616, Æthelfrith, pagan king of Northumbria, was killed in battle, and the Northumbrian throne was taken by Edwin, member of a rival dynasty, whom Æthelfrith had previously exiled. Bede notes that:

For all the time that Edwin reigned [616–633], the sons of the aforesaid, Æthelfrith, who had reigned before him, with many of the younger nobility, lived in exile among the Scots or Picts, and were there instructed according to the doctrine of the Scots, and were renewed with the grace of baptism.HE III, 1

AU places Eochaid Buide’s obit s.a. 629 (evidently about right, though various king-lists grant him a reign of only 15 to 17 years): “Death of Eochaid Buide son of Aedán, king of the Picts. Thus I have found in the Book of Cuanu.” There is no record of Eochaid’s career, so the claim that he was “king of the Picts” at the time of his death comes out of the blue. It may, of course, be a scribal error in the ‘Book of Cuanu’ – certainly, Eochaid Buide is not a listed king of the Picts.

Two years before Eochaid’s death, i.e. in 627, AU records: “The battle of Ard Corann [evidently in northern Ireland] in which fell Fiachna son of Demmán: the Dál Riata were victors.” Fiachna son of Demmán, king of the Ulaid, was the nephew of Baetán son of Cairell, to whom Eochaid’s father, Aedán, is said to have submitted. Perhaps it had been Fiachna’s intention to emulate his uncle and secure Eochaid’s submission – an ambition that cost him his life. According to AT, however, it was one Connad Cerr who led Dál Riata to victory. Further, AT refers to Connad as “king of Dál Riata”. In Scottish king-lists, Connad Cerr (Connad the Left-handed – Eochaid’s son?) is presented as Eochaid’s successor, and is allotted a reign of just three months. Assuming AT is not in error, it would seem that by 627 Eochaid was already sharing the rule of Dál Riata with Connad.

In 629 Connad Cerr, titled ‘king of Dál Riata’ in both AU and AT, was killed in a battle at Fid Eóin, another unidentified site in northern Ireland. Although king-lists grant him a reign of three months as Eochaid’s successor, in AU and AT his death is actually placed before Eochaid’s in the same annal.[*]

The thirteenth verse (of twenty-seven) of the Duan Albanach, a late-11th century, Irish, poetic king-list, runs:

Connad Cerr a quarter [of a year], illustrious in fame;

16 [years] for his son Ferchar;

after Ferchar, look at stanzas,

14 years of Domnall.

Other king-lists present a similar scheme, but it is not borne out by the annals, which imply that the reign of Domnall, i.e. Domnall Brecc (Domnall the Freckled) son of Eochaid Buide, directly followed that of Connad Cerr. The sole appearance of Ferchar son of Connad Cerr in the annals is his obit – only found in AU, placed s.a. 694, which seems implausibly late.

The annals report that, in 637, there took place a battle at Mag Rath (Moira, sixteen miles south-west of Belfast) in which Congal Caech, king of the Ulaid, was defeated and killed by Domnall son of Aed, of the Northern Uí Néill. Not mentioned by the annals, however, is the involvement of Domnall Brecc, who had allied himself with Congal Caech in opposition to Domnall son of Aed.[*] This is made apparent in a passage, seemingly taken directly from a book written by Cumméne, who was abbot of Iona (the seventh) from 657 to 669 (though it seems likely that he wrote his book in the 640s), which is found in the earliest extant manuscript of the Adomnán (ninth abbot of Iona, 679 to 704) ‘Life’ of St Columba[*]:

Cumméne the White, in the book which he wrote concerning the virtues of St Columba, thus said that St Columba began to prophesy as to Aedán and his posterity and his kingdom, saying: “Believe, O Aedán, without doubt, that none of thy adversaries will be able to resist thee unless thou first do wrong to me and to those who come after me. Wherefore do thou commend it to thy sons, that they also may commend to their sons and grandsons and posterity, lest through evil counsels they lose from out their hands the sceptre of this realm. For in whatever time they do aught against me, or against my kindred who are in Ireland [i.e. the Cenél Conaill], the scourge which I have endured from the Angel [see: above] in thy cause shall be turned upon them, by the hand of God, to their great disgrace, and men’s hearts shall be withdrawn from them and their enemies shall be greatly strengthened over them.”

Now this prophecy has been fulfilled in our times [i.e. Cumméne’s times] in the battle of Roth [i.e. Mag Rath], when Domnall Brecc, grandson of Aedán, devastated without cause the province of Domnall, grandson of Ainmire. And from that day to this they [Aedán’s family] have been held down by strangers[*] – a thing which convulses one’s breast and moves one to painful sighs.[*]

The year after Mag Rath (i.e. in 638), there was a battle at Glenn Mureson (unidentified) in which, notes AT: “the people of Domnall Brecc were put to flight”. AU and AT both record, although clearly too late (it is dated 678 by AU): “A battle in Calathros, in which Domnall Brecc was defeated.” Though not certainly identified, Calathros was later (736) the site of a battle between Dál Riata and the Picts of Fortriu, so perhaps Domnall Brecc’s opponents were also the Picts.

AU s.a. 642:

The death of Domnall son of Aed, king of Ireland, at the end of January. Afterwards Domnall Brecc was slain at the end of the year, in December, in the battle of Srath Caruin [Strathcarron], by Owain, king of the [Strathclyde] Britons. He reigned 15 years. [AT says he was “in the fifteenth year of his reign”.]

Both AU and AT repeat Domnall Brecc’s obit considerably later – s.a. 686 in AU, i.e. 44 years late. If the same degree of error applies to the late entry for the battle of Calathros, then that battle is plausibly placed in 634. Applying the same manipulation to the obit of Ferchar son of Connad Cerr, whose 16 year reign is said to have preceded Domnall Brecc’s, places his death in 650. By this token, Ferchar’s reign overlapped with Domnall Brecc’s.[*]

A fragment of Welsh verse (inserted into the poem Y Gododdin) commemorates Domnall Brecc’s death:

I saw a war-band, they came from Pentir [Kintyre],

And splendidly they bore themselves around the beacon.

I saw a second, they came down from their homestead:

They had risen at the word of Nwython’s grandson.

I saw stalwart men, they came at dawn,

And crows picked at the head of Dyfnwal Frych [Domnall Brecc].[*]

Meanwhile, in 634 Oswald, Æthelfrith’s son, had won the kingdom of Northumbria. Bede says that, “as soon as he ascended the throne”, Oswald:

… sent to the elders of the Scots, among whom himself and his followers, when in exile, had received the sacrament of baptism, desiring that they would send him a bishop, by whose instruction and ministry the English nation which he governed might learn the privileges and receive the Sacraments of the faith of our Lord.HE III, 3

Aidan, a monk of Iona, was consecrated and despatched to Northumbria. He established his see on the island of Lindisfarne. Bede notes:

… when the bishop, who was not perfectly skilled in the English tongue, preached the Gospel, it was a fair sight to see the king himself interpreting the Word of God to his ealdormen and thegns, for he had thoroughly learned the language of the Scots during his long exile.HE III, 3

AU reports that “the siege of Etin” took place in 638. Etin (Etain in AT) is normally identified as Din Eidyn (Fort of Eidyn), which is more familiar in the Anglicized form: Edinburgh. The annals do not say who was doing the besieging nor what its outcome was, and they tack it onto the end of their record of the battle of Glenn Mureson (one of, Dál Riatan king, Domnall Brecc’s defeats), but it is generally supposed that this brief report marks the capture of Edinburgh and the conquest of the British kingdom of Gododdin by Oswald.

Bede asserts that Oswald:

… obtained of the one God, Who made heaven and earth, a greater earthly kingdom than any of his ancestors. In brief, he brought under his dominion all the nations and provinces of Britain, which are divided into four languages, to wit, those of the Britons, the Picts, the Scots, and the English.HE III, 6

Having said that Oswald had “brought under his dominion” the Picts and Scots, Bede apparently contradicts himself, by saying (HE II, 5) it was Oswiu, Oswald’s brother, who succeeded him in 642, that: “for the most part subdued and made tributary the nations of the Picts and Scots, who occupy the northern parts of Britain”.

Later (HE III, 24), Bede states that Oswiu: “subdued the greater part of the nation of the Picts to the dominion of the English.” It would appear that Talorcan son of Eanfrith, king of the Picts from 653 to 657, was Oswiu’s nephew.[*] Bede says (HE I, 1) that, “when any question should arise”, the Picts: “choose a king from the female royal race rather than from the male”. It is widely suggested that, during the period of Edwin’s rule in Northumbria, when Oswiu and his brothers had been in exile, Eanfrith, the eldest brother (who ruled Bernicia, i.e. northern Northumbria, for a year after Edwin’s death), had married a Pictish princess, and, according to Pictish practice, as outlined by Bede, Talorcan succeeded to the throne in his own right. On the other hand, perhaps Oswiu had sufficient authority in the region to simply impose his nephew on the Picts, regardless of his eligibility. In any case, it seems reasonable to assume that Talorcan ruled as Oswiu’s subordinate. According to additional information supplied by AT to an entry dated 654 by AU, Talorcan son of Eanfrith secured a victory over Dál Riata at Srath Ethairt, an unidentified site, in which Dúnchad son of Conaing, who was apparently a grandson of Aedán son of Gabrán, and possibly joint king of Dál Riata, was killed.[*]

Oswiu died in 670. He was succeeded by his son, Ecgfrith. St Wilfrid’s biographer, Stephen, says that in the “early years” of Ecgfrith’s reign, “while the kingdom was still weak”, the “bestial tribes of the Picts” rebelled against Northumbrian overlordship. Ecgfrith rode to engage the Pictish army:

He slew an enormous number of the people, filling two rivers with corpses, so that, marvellous to relate, the slayers, passing over the rivers dry foot, pursued and slew the crowd of fugitives; the tribes were reduced to slavery and remained subject under the yoke of captivity until the time when the king [Ecgfrith] was slain.Vita Sancti Wilfrithi Ch.19

AU places the “expulsion” of Drest, king of the Picts, in 672. Scholars are generally in agreement that Drest’s expulsion was linked to the rebellion recorded by Stephen, but they are not in agreement in their interpretations of the circumstances – some envisage Drest as leader of the Picts’ rebellion against their Northumbrian overlords, whose expulsion was a consequence of Ecgfrith’s decisive victory; others see Drest as Oswiu’s puppet who was ousted by the Picts following his master’s death, which provoked Ecgfrith’s response.[*] Either way, Drest did not recover his throne – he died, presumably in exile, in 678. Drest’s successor was Bridei son of Beli.

A poem in a 10th century Irish ‘Life’ of Adomnán (Betha Adamnáin), said to have been composed by Adomnán, 9th abbot of Iona (d.704), himself, calls Bridei: “the son of the king of Ail Cluaithe.” Ail Cluaithe = Alt Clut, i.e. Dumbarton Rock, stronghold of the kings of the Strathclyde Britons. Bridei would seem to have been the brother of Owain, the king of the Strathclyde Britons who defeated and killed Domnall Brecc, king of the Dál Riatan Scots, in 642.[*]

In 681 the archbishop of Canterbury appointed one Trumwine as bishop of: “the province of the Picts, which at that time was subject to English [i.e. Northumbrian] rule.” (HE IV, 12). It later becomes apparent that Trumwine was based on the Northumbrian bank of the Forth – at Abercorn, approximately 3 miles west of Queensferry.

AU reports that, in 682: “The Orkneys were destroyed by Bridei [Bruide].” Maybe this was a reaction to the “siege of Dún Foither [identified as Dunnottar, on the east coast, near Stonehaven]” that had occurred (no detail is given) the previous year.

In 683 AU mentions: “The siege of Dún At [Dunadd, Argyll] and the siege of Dún Duirn [Dundurn, Perthshire].” Dunadd was in Dál Riata and Dundurn in Pictland – perhaps the two sieges are linked, indicating warfare between the Scots and the Picts.

In 685, Ecgfrith “rashly led his army to ravage the province of the Picts, greatly against the advice of his friends”, says Bede:

… the enemy [the Picts] made a feigned retreat, and the king [Ecgfrith] was drawn into the narrow passes of inaccessible mountains, and slain, with the greater part of the forces he had led thither, in the 40th year of his age, and the 15th of his reign, on the 13th of the Kalends of June [20th May].HE IV, 26

Bede doesn’t name the battle-site, but AU and AT do: “The battle of Dún Nechtain [Fort of Nechtan] was fought on the twentieth day of May, a Saturday”.[*] Bede doesn’t name Ecgfrith’s nemesis, but AT notes that Ecgfrith was killed by Bridei son of Beli (Irish: Bruide mac Bili), to whom it accords the title “king of Fortriu” – Fortriu being the region of Pictland traditionally, though not certainly, equated to Strathearn with Menteith – whilst the Historia Brittonum (§57) states:

Ecgfrith is the one who made war against his cousin, who was king of the Picts, named Bridei;[*] and there he fell with all the strength of his army, and the Picts with their king were victorious … It is called the battle of Llyn Garan [Crane Lake].

Symeon of Durham provides (LDE I, 9) the English name for the battle-site:

… he [Ecgfrith] was killed at Nechtanesmere, that is, the Lake of Nechtan … His body was buried in Iona, the island of Columba.

The Three Fragments – the remnants of an Irish chronicle – carry a poem which, though misplaced, obviously refers to the battle of Dún Nechtain:

Today Bridei fights a battle

over the land of his ancestor,

unless it is the wish of the Son of God

that restitution be made.

Today the son of Oswiu was slain

in battle against grey swords,

even though he did penance

and that too late in Iona [?].

Today the son of Oswiu was slain,

who used to have dark drinks;

Christ has heard our prayer

that Bridei would save the hills [?].[*]

Bede spells out the consequences of Ecgfrith’s catastrophic defeat:

From that time the hopes and strength of the English kingdom [i.e. Northumbria] began ‘to ebb and fall away’ [Virgil, Aeneid II, 169]; for the Picts recovered their own land which had been held by the English; and the Scots that were in Britain, and some part of the Britons, regained their liberty, which they have now enjoyed for about 46 years. Among the many English that then either fell by the sword, or were made slaves, or escaped by flight out of the country of the Picts, the most reverend man of God, Trumwine, who had been made bishop over them, withdrew with his people that were in the monastery of Aebbercurnig [Abercorn], which was situated in English territory but close by the firth [i.e. the Firth of Forth] that divides the lands of the English and the Picts.HE IV, 26

AU s.a. 693: “Bridei son of Beli, king of Fortriu, dies”. According to the 10th century Irish ‘Life’ of Adomnán (Betha Adamnáin): “the body of Bridei son of Beli, king of the Picts, was brought to Iona. A sore grief was his death to Adomnán”. Bridei was succeeded by Taran son of Entifidich. He was ejected from the kingship in 697, and was replaced by Bridei son of Derelei. Bridei died in 706, and was succeeded by his brother, Nechtan.

Meanwhile, Ecgfrith had been succeeded by his father’s illegitimate son, Aldfrith (d.705). According to later Irish genealogical tradition, Aldfrith’s mother was Fín or Fína, a princess of the Northern Uí Néill (who ruled north-western Ireland), and he was known to the Irish as Flann Fína. Aldfrith was a scholar of repute – “a man most learned in all respects” (HE V, 12); “wise-man [sapiens]” (AU s.a. 704) – and various Irish literary works, notably the Bríathra Flainn Fhína maic Ossu (Sayings of Flann Fína son of Oswiu), are attributed to him.

In the chronological run-down at the end of Bede’s Ecclesiastical History (HE V, 24) is the entry: “In the year 698, Berhtred, an ealdorman of the king of the Northumbrians, was slain by the Picts.” The Irish annals make it clear that Berhtred was killed in battle. Nevertheless, Bede, who lived through Aldfrith’s reign, notes that: “he nobly retrieved the ruined state of the kingdom, though within narrower bounds.” (HE IV, 26).

AU reports, s.a. 711: “A slaughter of the Picts by the Saxons in Mag Manonn [the Plain of Manu]”. The ‘Saxons’ were, of course, the Northumbrians. Bede states (HE V, 24): “In the year 711, Ealdorman (praefectus) Berhtfrith fought against the Picts.”[*] To which statement, Manuscripts D and E of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle add that the fighting took place between the rivers Avon and Carron – which join the Forth, on its southern bank, about twenty miles west of Edinburgh.[*] Manu is the Irish equivalent of the Welsh Manaw, and before the conquest of the British kingdom of Gododdin by the Northumbrian English, seven decades or so earlier, this region was known as Manaw Gododdin.

The inscription on the Brandsbutt Stone at Inverurie, Aberdeenshire, apparently reads (it is read from bottom to top): IRATADDOARENS.

The inscription on the Brandsbutt Stone at Inverurie, Aberdeenshire, apparently reads (it is read from bottom to top): IRATADDOARENS.