The Apocalypse Approaches III

Harold: A Second Judas Maccabeus

1053

Rhys ap Rhydderch (brother of Gruffudd) had evidently been mounting regular raids from southern Wales into England. He was killed on King Edward’s orders, and his head was presented to Edward, at Gloucester, on the 5th of January. Later in the year: “the Welshmen slew a great number of English folk of the guard” (ASC, MS C).[*]

Earl Godwine had fallen ill soon after his return to power in September 1052, but he had made a recovery. Godwine and his sons, Earl Harold, Tostig and Gyrth, were spending Easter 1053, with King Edward, at Winchester:

Then on the second Easter-day he [Godwine] was sitting with the king at a meal, when he suddenly sank down by the footstool, deprived of speech and of all his strength; and he was then removed into the king’s chamber;[*] and it was thought that it would pass over, but it was not so; but he continued so, speechless and strength-less, until the Thursday [15th April], and then resigned his life; and he lies there [at Winchester] within the Old Minster. —

confthree01

“I perceive,” said he [Godwine], “O king, that on every recollection of your brother, you regard me with angry countenance; but God forbid that I should swallow this morsel, if I have done anything which might tend either to his danger or your disadvantage.” On saying this, he was choked with the piece he had put into his mouth, and closed his eyes in death; and being dragged from under the table by Harold his son, who stood near the king, he was buried in the cathedral of Winchester.Henry of Huntingdon tells a version of the story (VI, 23) in which no mention is made of Alfred, but, instead, “the traitor Godwine” says:

“It has frequently been falsely reported to you, king, that I have been intent on your betrayal. But if the God of heaven is true and just, may He grant that this little piece of bread shall not pass my throat if I have ever thought of betraying you.” But the true and just God heard the voice of the traitor, and in a short time he was choked by that very bread, and tasted endless death.[*]Ailred of Rievaulx added an embellished version of the tale to his ‘Life’ of St Edward the Confessor[*]:

One day, on a popular festival, the king was sitting at the royal table in Godwine’s presence, and while they ate one of the waiters stumbled carelessly against some obstacle and very nearly fell, but bringing his other foot neatly forward, he regained his poise with no ill result. Several people remarked on this among themselves, congratulating him for bringing one foot to the aid of the other: the earl as if joking added: “So it is when a brother aids a brother, and one helps the other in his needs.”Ailred’s story was versified into French in a mid-13th century ‘Life’ of St Edward.[*] This verse ‘Life’, though, is best known for its illustrations, which are accompanied by separate brief, rubricated, descriptive verses.

The king replied: “So would my brother have helped me, if Godwine here had permitted.”

Godwine was afraid when he heard this, and showed a sad enough face. “I know, my king, I know that you still accuse me of your brother’s death, and you do not yet disbelieve those who call me a traitor to him and to you; but God knows all secrets and will judge. Let him make this morsel which I hold in my hand pass down my throat and leave me unharmed if I am innocent, responsible neither for betraying you nor for your brother’s murder.”

He said this, placed the morsel in his mouth, and swallowed it half way down his throat. He tried to swallow it further, and was unable: he tried to reject it, but it stuck firm. Soon the passage to his lungs was blocked, his eyes turned up, his limbs stiffened. The king watched him die in misery, and realising that divine judgement had come upon him, called to the bystanders: “Take this dog out”, he said. Godwine’s sons ran in, removed him from under the table and brought him to a bedroom, where soon afterwards he made an end fitting for such a traitor.

(Chapter 22)

|

The corpse of the felonous glutton Is dragged out of the house; He is immediately buried As befits an attainted traitor: By this account one can learn, Guilt is discovered after delay. |

— And his son Harold succeeded to his earldom [Wessex], and resigned that which he before had [East Anglia], and Ælfgar [son of Earl Leofric of Mercia] succeeded thereto.[*]Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscript C

In the strength of his body and mind Harold stood forth among the people like a second Judas Maccabeus: a true friend of his race and country, he wielded his father’s powers even more actively, and walked in his ways, that is, in patience and mercy, and with kindness to men of good will. But disturbers of the peace, thieves and robbers this champion of the law threatened with the terrible face of a lion.[*]Vita Ædwardi Regis (I, 5)

1054

In this year Earl Siward [of Northumbria] went with a great army into Scotland, and [on 27th July] made great slaughter of the Scots, and put them to flight; and the king [Macbeth] escaped. Many also fell on his [i.e. Siward’s] side, both Danish and English, and also his own son [named Osbeorn].[*]Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscript C

1055

Here in this year Earl Siward died; —

confthree02

In this year Earl Siward died at York, and his body lies within the minster at Galmanho, which he himself had before built, to the glory of God and all His saints.Manuscript D says Siward’s minster was: “hallowed in the name of God and St Olaf”. (It is assumed that the present St Olave’s Church, Marygate, stands on the site of Siward’s minster.) Henry of Huntingdon (VI, 24):

Siward, the stalwart earl, being stricken by dysentery, felt that death was near, and said, “How shameful it is that I, who could not die in so many battles, should have been saved for the ignominious death of a cow! At least clothe me in my impenetrable breastplate, gird me with my sword, place my helmet on my head, my shield in my left hand, my gilded battle-axe in my right, that I, the bravest of soldiers, may die like a soldier.” He spoke, and armed as he had requested, he gave up his spirit with honour.

— and then was summoned a full council-meeting [“at London”, MS C], 7 nights before mid-Lent [i.e. on 20th March]; and Earl Ælfgar was outlawed, because it was cast upon him that he was a traitor to the king and to all the people of the land. And he confessed it before all the men who were there gathered; though the word escaped him involuntarily. And the king gave to Tostig, son of Earl Godwine, the earldom which Earl Siward had before possessed.Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscript E

The exact nature of the charge against Ælfgar is not known, but Manuscript C insists that he was “outlawed without any guilt” (Florence of Worcester expresses the same view), whereas Manuscript D says he was “almost without guilt”. At any rate, Ælfgar went to Ireland, where he raised a force of eighteen ships’ companies. He then crossed over to Wales, and formed an alliance with Gruffudd ap Llywelyn, who was now ruler of all Wales.[*] Their joint forces marched into Herefordshire – the territory of King Edward’s French nephew, Earl Ralph.[*] On 24th October 1055, two miles from Hereford, Ælfgar and Gruffudd were intercepted by Ralph. Ralph had attempted to introduce his English forces to Continental cavalry tactics. Unfortunately, his attempt proved to be unsuccessful:

… before there was any spear shot the English folk fled, because they were on horses; and a great slaughter was made there, about four hundred men, or five; and on the other side not one.Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscript C[*]

The timid Earl Ralph … ordered the English, contrary to their custom, to fight on horseback. But just as they were about to join battle, the earl with his Frenchmen and Normans set the example by flight; the English seeing this, fled with their commander; and nearly the whole body of the enemy pursued them, slew 400 or five hundred of them, and wounded a great number.Florence of Worcester

Ælfgar and Gruffudd sacked and burned Hereford, including the cathedral – seven canons who defended the doors were killed.

In response, a force, drawn from all over England, was mustered at Gloucester, with Earl Harold in command. The invaders carried their booty back into Wales. Harold pursued them a little way across the border, but Ælfgar and Gruffudd had no intention of stopping to fight. Harold gave-up the chase, dismissed most of his force, returned to Hereford with the rest, and restored the town’s defences.

confthree00

Then a force was gathered from very near all England, and they came to Gloucester, and so went out, not far into Wales, and there lay some while. And Earl Harold meanwhile caused a ditch to be dug about the town [port, i.e. Hereford].Florence of Worcester:

… the vigorous Earl Harold … energetically pursued Gruffudd and Ælfgar, and boldly entering the Welsh borders encamped beyond Straddele; but they, knowing him to be a strong and warlike man, dared not risk a battle, but retreated into South Wales. On discovering this, he dismissed the greater part of his army there, with orders to manfully repel the enemy if circumstances should require; and returning with the remainder to Hereford, encircled it with a broad and deep ditch, and fortified it with gates and bars.The implication would seem to be that Hereford had not previously been a fortified town (burh), but this is not the case. ‘Herefordshire Archaeology Report 310’ (January 2013, freely available online):

• 9th century. The first defended town, its gravel and clay rampart and ditch demonstrated by excavation on the west and north sides but the putative eastern side returning down the eastern side of the Cathedral Close remaining unproven.

• c.900AD. The town was refortified with a turf, clay and timber rampart extended well to the east (proved by excavations at Cantilupe Street) to include the St Guthlac’s site. The defences were strengthened by stone walls later in the 10th century.

• Late 10th to 11th century. There is evidence from both the west and east sides of the city for the neglect or abandonment of the defences before an episode of refurbishment involving the re-excavation of the ditch to the west and the provision of a timber fence or palisade on the east. These may be associated with the documented refortification of the city in 1055. Recent C14 dates from the Bishop’s Meadow Row Ditch south of the river suggest it may date from the same episode.

Eventually, Harold, Ælfgar and Gruffudd agreed terms at a place called Billingsley:

And Earl Ælfgar was then inlawed, and there was restored to him all that had before been taken from him. And the fleet went to Chester, and there awaited their pay, which Ælfgar had promised them.Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscript C

1056

On 10th February, the bishop of Hereford, Athelstan, died:

… and Leofgar was appointed bishop. He was Earl Harold’s mass-priest; he wore his moustaches in his priesthood until he was a bishop. He forsook his chrism and his rood, his spiritual weapons, and took to his spear and to his sword after his bishophood, and so went campaigning against Gruffudd [Griffin], the Welsh king; and he was there slain, and his priests with him, and Æthelnoth the sheriff, and many good men with them; and the others fled away.[*] This was 8 nights before Midsummer [i.e. on 16th June]. It is difficult to describe the misery, and all the marches, and the encamping, and the labour, and the destruction of men, and also of horses, which all the English army underwent, until Earl Leofric came there, and Earl Harold and Bishop Ealdred [of Worcester], and made peace between them; so that Gruffudd swore oaths, that he would be to King Edward a faithful and unfailing under-king. And Bishop Ealdred succeeded to the bishopric that Leofgar had before had for 11 weeks and 4 days.Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscript C

confthree03

The passage itself was difficult from the violence of the waves, but it was not from that cause that the contest arose; Llywelyn asserted his superiority, Edward his equality; Llywelyn that all England, with Cornwall, Scotland and Wales, had been conquered from the giants by his forefathers, whose direct heir he claimed to be. Edward that his own ancestors had received them from their conquerors. After this contest had been long continued, Edward at last entered a boat to approach Llywelyn. The Severn is there a mile in breadth. Llywelyn observing and recognizing him, threw off his mantle of state, for he had attired himself for the dispensation of justice, and entered the water up to his breast; when, cordially seizing the boat, he exclaimed, “Most prudent king, your humility has gained the victory over my pride, and your wisdom has triumphed over my absurdity; mount then the neck which I so foolishly erected against you, and thus you shall enter the land which your courtesy has this day made your own.” Thus, having taken Edward upon his shoulders, Llywelyn made him sit upon the mantle, and with clasped hands did him homage. This was a remarkable beginning of peace; but after the way of the Welsh, it was observed only until an opportunity of doing injury arrived.De Nugis Curialium II, 23

1057

Back in 1054 Bishop Ealdred had gone “to Cologne, over sea, on the king’s errand” (MS D). Florence of Worcester explains that the purpose of Ealdred’s mission was to enlist the aid of Emperor Henry III in arranging the return to England, from Hungary, of Edward, the exiled (by King Cnut in 1017) son of Edmund Ironside, King Edward’s half-brother, because, asserts Florence: “the king had determined to make him heir to the kingdom”. In 1057:

In this year came the ætheling Edward to England; he was King Edward’s brother’s son, King Edmund who was called Ironside for his valour… We know not for what cause it was done that he might not see [the face] of his kinsman King Edward. Alas! that was a rueful hap, and harmful for all this nation, that he so quickly ended his life after he came to England, to the misfortune of this poor nation.Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscript D

The ætheling Edward, who is generally known as Edward the Exile, died on 19th April, and was buried in St Paul’s, London[*]. Perhaps he was already sick when he arrived in England, and that was the, perfectly innocent, reason he was not allowed to meet the king. We shall never know. It appears that the ætheling was accompanied by his wife, Agatha (“the emperor’s kinswoman”, MS D), his daughters, Margaret and Christina, and his son Edgar, and that they remained in England after his death.

Two other notable deaths in 1057 were those of Earl Leofric, on either 31st August or 30th September[*], and Earl Ralph, on 21st December. Earl Ralph was buried at Peterborough, and Earl Leofric:

… was buried with great state at Coventry. Among his other good deeds in this life, he and his wife, the noble countess Godgifu (comitissa Godgiva), who was a devout worshipper of God, and one who loved the ever-virgin St Mary, entirely constructed at their own cost the monastery there, well endowed it with land, and enriched it with ornaments to such an extent, that no monastery could be then found in England possessing so much gold, silver, jewels, and precious stones. [A list of their numerous endowments to various religious establishments follows] … As long as he lived, this earl’s wisdom stood the kings and people of England in good stead.Florence of Worcester

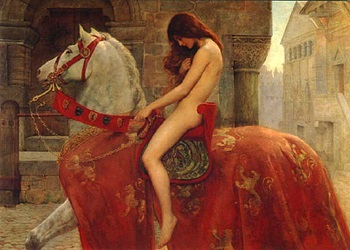

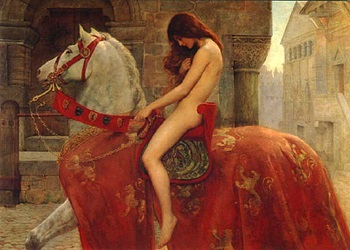

Leofric’s wife, Godgifu[*], is much better known than the earl himself, as Lady Godiva.

confthree04

13th century chronicler Roger of Wendover tells, s.a. 1057, the earliest known version of a famous fable:

13th century chronicler Roger of Wendover tells, s.a. 1057, the earliest known version of a famous fable:

The countess Godiva, who was a great lover of God’s mother, longing to free the town of Coventry from the oppression of a heavy toll, often with urgent prayers besought her husband, that from regard to Jesus Christ and his mother, he would free the town from that service, and from all other heavy burdens; and when the earl sharply rebuked her for foolishly asking what was so much to his damage, and always forbade her ever more to speak to him on the subject; and while she, on the other hand, with a woman’s pertinacity, never ceased to exasperate her husband on that matter, he at last made her this answer, “Mount your horse, and ride naked, before all the people, through the market of the town, from one end to the other, and on your return you shall have your request.” On which Godiva replied, “But will you give me permission, if I am willing to do it?” “I will,” said he. Whereupon the countess, beloved of God, loosed her hair and let down her tresses, which covered the whole of her body like a veil, and then mounting her horse and attended by two knights, she rode through the market-place, without being seen except her fair legs; and having completed the journey, she returned with gladness to her astonished husband, and obtained of him what she had asked; for Earl Leofric freed the town of Coventry and its inhabitants from the aforesaid service, and confirmed what he had done by a charter.The character Peeping Tom, apparently, became attached to the yarn in the 17th century.

And Earl Leofric died, and Ælfgar, his son, succeeded to the earldom which his father before had [i.e. Mercia].Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscript E

Ælfgar’s old earldom, East Anglia, was given to Gyrth, the brother of earls Harold and Tostig. Another brother, Leofwine, gained an earldom in the southeast. Herefordshire was acquired by Harold.[*] With most of England under the control of Godwine’s sons, it would not be surprising if Ælfgar felt somewhat insecure and isolated. Maybe this prompted him to strengthen his ties with his western neighbour, Gruffudd ap Llywelyn – at some stage Ælfgar married-off his daughter, Ealdgyth, to Gruffudd – which in turn led to him being, once again, outlawed.

1058

In this year Earl Ælfgar was banished; but he soon came in again with force, through Gruffudd’s aid. And this year came a ship-army from Norway. It is tedious to tell how it all went.Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscript D

Florence of Worcester supplies a little more clarity than the evidently bored author of Manuscript D:

Ælfgar, earl of the Mercians, was a second time outlawed by King Edward; but assisted by Gruffudd, king of the Welsh, and supported by a Norwegian fleet, which came to him unexpectedly, he soon recovered his earldom by force.

According to the Irish Annals of Tigernach, the Norwegian assault on England amounted to nothing short of a full-scale invasion:

A fleet [was led] by the son of the king of Norway, with the foreigners [i.e Norsemen] of the Orkneys and the Hebrides and Dublin, to seize the kingdom of England; but to this God consented not.

Whilst Welsh annals report that:

Magnus, son of Harald [King Harald III of Norway, i.e. Harald Hardrada], ravaged the lands of the English, with the assistance of Gruffudd, king of the Britons.Annales Cambriae B-text

Presumably the situation was defused by “tedious” diplomatic means – no doubt involving a considerable contribution to the Norwegian exchequer, as well as Ælfgar’s restoration – otherwise, one must assume, if it had come to all-out war and great loss of life, the English chronicler would have been interested enough to make a note of it.

In 1052, Stigand, archbishop of Canterbury, had acquired his position in irregular circumstances and his appointment had not been recognized by Rome. In 1058, however, Benedict X, the antipope (April 1058 – January 1059), sent him a pallium. When Benedict was deposed, by Pope Nicholas II, Stigand once more became persona non grata.[*]

1059–1062

There is little recorded incident in these years.

The Vita Ædwardi Regis comments (I, 6):

… when Earl Tostig ruled the earldom [of Northumbria], the Scots, since they had not yet tested him and consequently held him more cheaply [than they had Earl Siward], harassed him often with raids rather than war. But this irresolute and fickle race of men, better in woods than on the plain, and trusting more to flight than to manly boldness in battle, Tostig, sparing his own men, wore down as much by cunning schemes as by martial courage and military campaigns. And as a result they and their king preferred to serve him and King Edward than to continue fighting, and, moreover, to confirm the peace by giving hostages.

This peace between King Edward and Earl Tostig, on one side, and the Scots’ king, Malcolm III, on the other, was evidently ratified in 1059, when Tostig, Cynesige, archbishop of York, and Æthelwine, bishop of Durham, escorted Malcolm to meet with the English king[*]. The meeting-place is not recorded, but it was apparently in northern England – Geffrei Gaimar noting that Edward “drew near”, whilst Malcolm was conducted “beyond the Tweed”:

He came to meet King Edward.

He [Edward] had speech with Malcolm.

Presents he [Edward] gave him; much he honoured him …

Peace and truce they took between them.lines 5093–5095 & 5097

Archbishop Cynesige died on 22nd December 1060.

In the spring of 1061, Bishop Ealdred, newly appointed archbishop of York, travelled to Rome, in the company of Earl Tostig, to collect his pallium. It seems that the earl had an able lieutenant, named Copsig, to govern Northumbria for him[*]. Whilst Tostig was abroad, however:

… Malcolm, king of Scots, furiously ravaged the earldom of his sworn brother Earl Tostig, and violated the peace of St Cuthbert in the island of Lindisfarne.Symeon of Durham HR s.a. 1061

There was evidently no military retaliation. Gaimar says (line 5117) that “peace was made with Malcolm” when Tostig returned, and the incident would appear not to have permanently soured relations between the Scots’ king and “his sworn brother” Tostig.

confthree05

Though his passing is not recorded, it seems likely that Earl Ælfgar of Mercia died during 1062 (he simply disappears from the record), and was succeeded by his eldest son, Edwin.[*]

1063

Perhaps Ælfgar’s death gave Earl Harold the opportunity he had been waiting for: to destroy the Mercian earl’s Welsh ally, Gruffudd ap Llywelyn. Chronicle Manuscript D:

In this year, after Midwinter [i.e. after Christmas 1062], Earl Harold went from Gloucester to Rhuddlan, which was Gruffudd’s, and burned the residence, and his ships, and all the equipments which belonged thereto, and put him to flight. —

— And then, at the Rogation days [26th–28th May 1063], Harold went with ships from Bristol around Wales [Brytlande], and the folk made peace and gave hostages. And Tostig went with a land-force against them, and they subdued the land. —

— But in the same year, at harvest, King Gruffudd was slain, on the Nones of August [the 5th of August], by his own men, because of the war which he warred against Earl Harold. He was king over all the-Welsh-race [Wealcyn]; and his head was brought to Earl Harold, and Harold brought it to the king, and his ship’s figure-head, and the ornaments with it. And King Edward delivered the land over to his two brothers, Bleddyn and Rhiwallon; and they swore oaths, and gave hostages to the king and to the earl, that they would be faithful to him in all things, and ready to [serve] him everywhere by water and by land, and to pay such requisitions from the land as had been done before to any other king.[*]Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscript D

… Gruffudd ap Llywelyn was slain, after innumerable victories and taking of spoils and treasures of gold and silver and precious purple raiment, through the treachery of his own men, after his fame and glory had increased and after he had aforetimes been unconquered, but was now left in the waste valleys, and after he had been head and shield and defender to the Britons.Brut y Tywysogion (Peniarth MS 20)

confthree06

The recent history of the English tells how, when the Britons had made an irruption and were ravaging England, Duke Harold was sent by the most pious King Edward to subdue them. He was an able warrior with an illustrious record of praiseworthy achievements, and one who might have transmitted his own glory and that of his family to future generations had he not imitated the wickedness of his father and tarnished his titles of merit by disloyally assuming the crown. When, therefore, he discovered the nimbleness of the nation he had to deal with, he selected light-armed soldiers so that he might meet them on equal terms. He decided, in other words, to campaign with a light armament shod with boots, their chests protected with straps of very tough hide, carrying small round shields to ward off missiles, and using as offensive weapons javelins and a pointed sword. Thus he was able to cling to their heels as they fled and pressed them so hard that “foot repulsed foot and spear repulsed spear,” and the boss of one shield that of another. And so he reached Snowdon, the Hill of Snows itself, and wasted the whole country, and prolonging the campaign to two years, captured their chiefs and presented their heads to the king who had sent him; and slaying every male who could be found, even down to the pitiful little boys, he thus pacified the province at the mouth of the sword.[*] He established a law that any Briton who was found with a weapon beyond a certain limit which he set for them, to wit the Fosse of Offa [Offa’s Dyke], was to have his right hand cut off by the officials of the king. And thus by the valour of this leader the power of the Britons was so broken that almost the entire race seemed to disappear and by the indulgence of the aforesaid king, their women were married to Englishmen.Norman-Welsh author Giraldus Cambrensis, in his Description of Wales (Descriptio Cambriae, 1194), writes (II, 7):

He [Harold] advanced into Wales on foot, at the head of his lightly-clad infantry, lived on the country, and marched up and down and round and about the whole of Wales with such energy that he “left not one that pisseth against a wall”. In commemoration of this success, and to his own undying memory, you will find a great number of inscribed stones put up in Wales to mark the many places where he won a victory. This was the old custom. The stones bear the inscription: HIC FUIT VICTOR HAROLDUS [‘Harold was the victor here’].No such inscribed stones have been found.

The unified Welsh kingdom of Gruffudd ap Llywelyn died with him. The north was in the hands of his maternal half-brothers, Bleddyn and Rhiwallon, sons of Cynfyn. Rule of the south-west reverted to the descendants of Hywel Dda, in the person of Maredudd ab Owain ab Edwin – nephew of Hywel ab Edwin, who had been killed in battle by Gruffudd ap Llywelyn in 1044. Whilst the dominant force in the south-east was Caradog – son of Gruffudd ap Rhydderch, who had been killed by Gruffudd ap Llywelyn in 1055.

confthree07

It happened in the same year [i.e. 1063] that in the king’s presence in the royal hall at Windsor, just as his brother Harold was serving wine to the king, Tostig grabbed Harold by the hair. For Tostig nourished a burning jealousy and hatred because, although he was himself the first-born [no he wasn’t, Harold was the older], his brother was higher in the king’s affection. So, driven by a surge of rage, he was unable to check his hand from his brother’s flowing locks. The king, however, foretold that their destruction was already approaching, and that the wrath of God would be delayed no longer. Such was the savagery of those brothers that when they saw any village in a flourishing state, they would order the lord and all his family to be murdered in the night, and would take possession of the dead man’s property. And these, if you please, were justices of the realm! So Tostig, departing in anger from the king and from his brother, went to Hereford, where his brother had prepared an enormous royal banquet. There he dismembered all his brother’s servants, and put a human leg, head, or arm into each vessel for wine, mead, ale, spiced wine, wine with mulberry juice, and cider. Then he sent to the king, saying that when he came to his farm he would find enough in salted food, and that he should take care to bring the rest with him. For such an immeasurable crime the king commanded him to be outlawed and exiled.The earlier part of this fable was adopted by Ailred of Rievaulx, in his 1163 ‘Life’ of St Edward the Confessor (Ch.21). Ailred, however, shifted the incident to when Harold and Tostig were children. They have a fierce fight, at a banquet in front of the King and Godwine: “Now Harold made a stronger onslaught on his brother, seized his hair with both hands, dragged him to the ground, and would have throttled him with his greater strength, had he not been quickly rescued.” King Edward then prophesies the fate of the brothers.

Right: The fight between Harold and Tostig as depicted in the mid-13th century verse ‘Life’ of St Edward (Cambridge University Library MS Ee.iii.59).

Right: The fight between Harold and Tostig as depicted in the mid-13th century verse ‘Life’ of St Edward (Cambridge University Library MS Ee.iii.59).

Above: The fight between Harold and Tostig as depicted in the mid-13th century verse ‘Life’ of St Edward (Cambridge University Library MS Ee.iii.59).

Above: The fight between Harold and Tostig as depicted in the mid-13th century verse ‘Life’ of St Edward (Cambridge University Library MS Ee.iii.59).

1064

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records no events pertaining to 1064.

1065

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscript D:

Here in this year, before Lammas [1st August], Earl Harold ordered a building to be erected in Wales at Portskewett [in Gwent], when he had subdued it; and there gathered much property, and thought to have King Edward there for the sake of hunting. But when it was all ready,[*] then went Caradog, the son of Gruffudd [ap Rhydderch], with all the gang which he could get, and slew almost all the folk who were there building, and took the property which was there prepared. We know not who first counselled this folly [unræd].[*] This was done on St Bartholomew’s mass-day [24th August].

confthree08

Manuscript D continues:

— [*] And soon after this, all the thegns in Yorkshire and in Northumberland gathered together and outlawed their earl Tostig,[*] and slew all the men of his court that they could come at, both English and Danish, and took all his weapons at York, and gold and silver, and all his moneys which they could anywhere hear of …

Whilst Manuscript C says:

And then, after Michaelmas [29th September], all the thegns in Yorkshire went to York, and there slew all Earl Tostig’s housecarls whom they could hear of, and took his treasures… all his earldom unanimously renounced and outlawed him, and all who raised up lawlessness with him, because he first robbed God, and bereaved all those of life and of land over whom he had power.

Florence of Worcester provides further detail:

Shortly after the feast-day of St Michael the archangel, to wit, on Monday the 5th of the Nones of October [the 3rd of October], the Northumbrian thegns Gamelbearn, Dunstan son of Æthelnoth, Glonieorn son of Heardwulf, entered York with 200 soldiers, and (in revenge for the execrable slaughter of the noble Northumbrian thegns Gospatric – whom Queen Edith, for the sake of her brother Tostig, had ordered to be treacherously slain in the king’s court, on the 4th night after the feast of our Lord’s Nativity [i.e. on 28th December 1064] – and Gamel son of Orm and Ulf son of Dolfin – whom Earl Tostig, while at York, the year before, had caused to be treacherously slain in his own chamber, although there was peace between them – and also on account of the heavy tribute which he unjustly laid on the whole of Northumbria) they on the same day, first of all, stopped in their flight his [Tostig’s] Danish housecarls Amund and Ravenswart, and put them to death outside the city walls, and on the following day slew more than 200 men of his court, on the north side of the river Humber. They also broke open his treasury, and retired, carrying off all his effects.

Returning to Chronicle Manuscript D (and E):

… and [the Northumbrians] sent after Morcar, son of Earl Ælfgar, and chose him for their earl. And he went south with all the shire, and with Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire and Lincolnshire, until he came to Northampton; and his brother Edwin came to meet him with the men that were in his earldom [i.e. Mercia], and also many Welsh [Bryttas] came with him.

Earl Tostig himself was in Wiltshire, “at Britford with the king” says Manuscript C.

The king despatched (at Tostig’s request, says Florence of Worcester) an embassy, headed by Earl Harold, to negotiate with the rebels.

There [i.e. at Northampton] came Earl Harold to meet them, and they laid an errand on him to King Edward, and also sent messengers with him, and asked that they might have Morcar for their earl… And the northern men did great harm about Northampton while he went on their errand, inasmuch as they slew men, and burned houses and corn, and took all the cattle which they could come at; that was many thousand. And many hundred men they took, and led north with them; so that the shire, and the other shires which are nigh there, were for many winters the worse.Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscripts D and E

The Vita Ædwardi Regis makes no mention of Northampton, nor or of Harold’s involvement, but says that, the rebels (“gathered together in an immense body, like a whirlwind or tempest”) made their way as far south as Oxford (on the Mercia/Wessex border). In Manuscripts D and E of the Chronicle the rebels never move beyond Northampton. It is clear from Manuscript C, however, that Harold met with the rebel leaders at Northampton initially, but subsequently at Oxford. At any rate, in the Vita, on their first meeting with the rebels, King Edward’s unnamed messengers told them that if they called-off “the madness” any proven injustices would be rectified:

But those in revolt against their God and king rejected the conciliatory message, and replied to the king that either he should straightway dismiss that earl of his [i.e. Tostig] from his person and the whole kingdom, or he himself would be treated as an enemy and have all them as enemies. And when the most gracious king had a second and third time through messengers and by every kind of effort of his counsellors tried to turn them from their mad purpose, and failed, he moved from the forests, in which he was as usual staying for the sake of regular hunting, to Britford, a royal manor near the royal town of Wilton. And when he had summoned the magnates from all over the kingdom, he took counsel there on what was to be done in this business.Vita Ædwardi Regis I, 7

It appears that there was little support for Tostig at the meeting, several of those present seemingly sharing the rebels’ view that he was cruel and rapacious. Further:

It was also said, if it be worthy of credence, that they [the Northumbrians] had undertaken this madness against their earl at the artful persuasion of his brother, Earl Harold (which heaven forbid!). But I dare not and would not believe that such a prince was guilty of this detestable wickedness against his brother. Earl Tostig himself, however, publicly testifying before the king and his assembled courtiers charged him with this; but Harold, rather too generous with oaths (alas!), cleared this charge too with oaths.Vita Ædwardi Regis I, 7

The Northumbrian rebels persisted in their demand for Tostig to be removed from office. Edward attempted to mobilise an army to crush them:

But because changeable weather was already setting in from hard winter, and it was not easy to raise a sufficient number of troops for a counter-offensive, and because in that race horror was felt at what seemed civil war, some strove to calm the raging spirit of the king and urged that the attack should not be mounted. And after they had struggled for a long time, they did not so much divert the king from his desire to march as, wrongfully and against his will, desert him. Sorrowing at this he fell ill, and from that day until the day of his death he bore a sickness of mind.Vita Ædwardi Regis I, 7

Anyway, Edward was forced to concede. On 28th October, at Oxford, Harold informed the rebels that Morcar would be earl of Northumbria, and, say Manuscripts D and E, “he [Harold] renewed there Cnut’s law”, i.e. justice was restored.[*]

… and after the feast of All Saints [1st November], with the assistance of Earl Edwin, they banished Tostig from England …Florence of Worcester

And Earl Tostig, and his wife, and all those who wanted what he wanted, went south over sea with him to Earl Baldwin [i.e. Count Baldwin V of Flanders], and he received them all, and they were all winter there [“at Saint-Omer”, MS C].[*]Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscripts D and E

And King Edward came to Westminster at Midwinter, and there caused the minster to be hallowed, which he himself had built to the glory of God and St Peter, and to all God’s saints; and the church-hallowing was on Childermas-day [28th December]. —

— And he died on Twelfth-day eve [5th January 1066],[*] and was buried on Twelfth-day [6th January], in the same minster …Anglo-Saxon Chronicle Manuscripts C and D

confthree09

|

| In the church of Westminster, Which King Edward caused to be restored, Is his body buried. A deformed man there is cured; So God does many cures Through Edward, who is his loyal servant. |

And so the building, nobly begun at the king’s command, was successfully made ready; and there was no weighing of the costs, past or future, so long as it proved worthy of, and acceptable to, God and St Peter. The house of the high altar, noble with its most lofty vaulting, is surrounded by dressed stone evenly jointed. Also the passage round that temple is enclosed on both sides by a double arching of stone with the joints of the structure strongly consolidated on this side and that. Furthermore, the crossing of the church, which is to hold in its midst the choir of God’s choristers, and to uphold with like support from either side the high apex of the central tower, rises simply at first with a low and sturdy vault, swells with many a stair spiralling up in artistic profusion, but then with a plain wall climbs to the wooden roof which is carefully covered with lead. Above and below are built out chapels methodically arranged, which are to be consecrated through their altars to the memory of apostles, martyrs, confessors, and virgins. Moreover, the whole complex of this enormous building was started so far to the East of the old church that the brethren dwelling there should not have to cease from Christ’s service and also that a sufficiently spacious vestible might be placed between them.

| William of Malmesbury notes (GR II §228) that Edward was buried: “in the said church, which he, first in England, had erected after that kind of style which now almost all attempt to rival at enormous expense.”

Below: Westminster Abbey (with work still in progress), as depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry.

|

|

| Right: Westminster Abbey (with work still in progress), as depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry. |

Manuscripts C and D of the Chronicle commemorate Edward’s death in verse, and then, in a masterpiece of understatement, add:

And here also Earl Harold was hallowed king; and he experienced little quiet therein, the while that he ruled the realm.