THE IRON AGE

c. 800 BC – AD 43

1: Times Change

Until very recently, the Iron Age was described as a time when Britain was subject to a succession of invasions, by Celts from mainland Europe[*]. These invasionist theories, however, and the notion that Britain was absorbed into a pan-European ‘Celtic civilisation’, have been found wanting:

There was no cross-European Celtic people. There was no broad-based Celtic art, society or religion. And there were never any Celts in Britain.John Collis (‘Celtic Fantasy’, British Archaeological News 11, March 1994)

… our views of the Iron Age have seen radical change and controversy in a flourish of new research over the last ten years… No one is denying that people in Iron Age Britain spoke Celtic languages, or shared certain common cultural traditions with their contemporaries in mainland Europe, such as the use of La Tène ‘art’.[*] What has been shown to be untrue, however, is that there existed a single Celtic race whose members all had the same religion, psychological traits, and type of society, and who recognised themselves as ‘Celts’… While there were contacts, and shared cultural elements across Europe, it is the differences in all aspects of life between neighbouring areas that seem to have been more important than the similarities.J.D. Hill (‘Weaving the strands of a new Iron Age’, British Archaeology 17, September 1996)

Archaeologists widely agree on two things about the British Iron Age: its many regional cultures grew out of the preceding local Bronze Age, and did not derive from waves of continental ‘Celtic’ invaders. And secondly, calling the British Iron Age ‘Celtic’ is so misleading that it is best abandoned.Simon James (‘Peoples of Britain’, BBC History, 1998)

Iron making know-how was probably introduced into Britain, not by a hoard of invading Celtic warriors, but through normal, non-hostile, contacts with the Continent. Although iron ores were far more common (hence cheaper) than those of copper and, particularly, tin, wrought iron wasn’t necessarily better than bronze, and turning ore into usable object was a considerably more laborious procedure[*]. There is evidence to suggest that ironworking was taking place in Britain (at Hartshill Quarry, Berkshire) as early as the 10th century BC[*]. The first extant iron objects, however, are from a couple of centuries later – such as those from the, so called, Llyn Fawr Hoard.[*] As a consequence, the phrase ‘Llyn Fawr phase’ is sometimes used to describe the period, c.800 BC–c.600 BC, of the Bronze Age to Iron Age transition.[*] Iron did not completely displace bronze of course. Bronze production continued, though on a much smaller scale, being used for vessels, horse-harness fittings and decorative items.

Hillforts are defended enclosures, usually, as the name suggests, built on a hill-top. There are more than three thousand sites in Britain that fall into the broad category of hillfort. Most are found in central, southern and western England, Wales and south-eastern Scotland. They come in diverse shapes and a vast range of sizes. Some have just one circuit of defences (univallate), whilst others have more (multivallate). At most sites, the circuits comprise a rampart and a ditch (being defensive structures, the ditch is outside the rampart), but at some they are formed of ramparts only. The ramparts themselves were constructed using various methods and materials.

iron01

Some sites categorised as hillforts are actually built on relatively flat ground. They are sometimes described as ‘plateau forts’, and, getting no advantage from natural features, rely entirely on man-made defences.[*] The entrances (there are usually one or two, which would have had timber gates) are the weak points in a hillfort’s defences, so much ingenuity and energy was often devoted to their design and construction. The entrance earthworks can be complex, and might incorporate long passages, bastions, barbicans, guardrooms, overlapping ramparts, hornworks and outworks.[*]

All this variety and complexity is, however, the product of some eight centuries of hillfort evolution. Monuments recognized as hillforts emerge towards the end of the Bronze Age, c.900 BC, but it was not for another century or two that the main phase of building began[*]. Generally, early hillforts were relatively simple, univallate, affairs. Around 400 BC many of them were abandoned. A few, however, not only continued in use, but received elaborate enhancements, such as multivallate defences and labyrinthine entrance passages. A possible explanation is that the abandoned hillforts belonged to tribal groups whose lands were annexed by stronger neighbours. These dominant groups developed their own hillforts as a demonstration of their strength. Indeed, like a modern corporate skyscraper, ‘developed hillforts’ appear to be designed as much for their impressive appearance, as for their actual purpose.

iron02

Maiden Castle, near Dorchester, in Dorset, is the largest developed hillfort in Britain. In the Neolithic, there had been a ‘causewayed enclosure’ at the eastern end (bottom-left in the aerial photo) of the site, and then a large ‘bank barrow’ (about 545 metres by 19 metres) had been erected, running east–west across the centre of the hill.[*] Around 600 BC, more or less on top of the old causewayed enclosure, a univallate, ditch and rampart (utilising dump and timber-revetted box rampart techniques), hillfort was built.[*] Between c.400 BC and c.100 BC, the hillfort underwent several phases of development, to produce the massive glacis ramparts and complex entrances which are still impressive today. The enclosed area of the developed hillfort, over 17 hectares, is almost triple that of the original fortification, and the overall size of the site is in excess of 45 hectares. Sir Mortimer Wheeler excavated at Maiden Castle in the mid-1930s. Based on his findings, Sir Mortimer produced a famously dramatic description of Maiden Castle’s fall to the Romans, led by, the future emperor, Vespasian, in their westward advance after the invasion of AD 43. Further excavation, by Niall Sharples, took place in the mid-1980s, and a new appraisal of the evidence suggested that, by the time the Romans arrived, the hillfort had already outlived its usefulness – its defences were neglected and its population was much-reduced.[*] What seems clear, however, is that Maiden Castle was finally abandoned within a few decades of the Roman conquest. A small Romano-British temple was built within the interior in the late-4th century AD.[*]

Pembrokeshire Coast National Park.

Pembrokeshire Coast National Park.

In total contrast to Maiden Castle is Castell Henllys, in Pembrokeshire, which only encloses about ½ hectare.[*] Maiden Castle is classed as a ‘contour fort’ – its defensive circuits follow the contours of the hill on which it is superimposed. Castell Henllys, however, is a ‘promontory fort’. A promontory site provides a hillfort with natural defences for much of its perimeter, requiring extensive man-made defences only across the neck of land joining it to the adjacent area. (If the promontory in question juts out into the sea, then the fort is often called a ‘cliff castle’). Castell Henllys is built on a small spur overlooking the River Gwaun. There are precipices to the east, south and west, so most of its man-made defences are directed towards the north. These defences comprise a large inner bank, a ditch, a smaller outer bank and another ditch. The earthworks curve round to meet the precipice at the east, and at the west they merge at the place where the entrance was. Thirty metres north of the fort is an outer bank and ditch. Beneath the bank, archaeologists discovered a band of upright stones. The rows of stones, which are called a ‘chevaux-de-frise’, and are rare in Britain, would have impeded a mass attack, and provided a defence against chariots. Nevertheless, at some point in the hillfort’s evolution, they became superfluous, and the bank was thrown up on top of them. Castell Henllys was occupied from c.400 BC to c.100 BC. It was, seemingly, crowded with roundhouses, and may have had a population of 100–150 people. A lack of evidence for preliminary food processing, e.g. threshing, butchery, might imply that Castell Henllys was home to the local elite – prepared foodstuffs being brought into the hillfort by lower status families from the surrounding countryside.

iron03

The first phase of settlement on the promontory was rapidly enclosed by a palisade with uprights set in a continuous stone-packed trench… In the northwest, a complex series of five entrance gateways rapidly replaced each other over c.40 years …p.49

It is highly probable that the chevaux-de-frise belongs to the palisaded phase, but this cannot be demonstrated with absolute certainty …p.50

The width of the chevaux-de-frise would have been sufficient to slow a charging Iron Age horse (the size of a modern pony), which might have had difficulty in clearing such a spread of stones, but they were hardly a major deterrent… It is possible that the chevaux-de-frise primarily served a symbolic role, marking the boundary of the settlement and the approach to the fort.p.99

As there is no evidence of post replacement despite good preservation of the palisade and packing in several locations, the palisade only had the life of one generation of timbers. The length of time that the palisade posts would survive in this soil can be estimated from the experimental work on the site; this suggests a life for the palisade of only a few decades. Within this time, numerous changes were made at the entrance. This indicates that these changes were not forced on the builders by the decay of posts and need for rebuilding, but rather they were part of an evolution of design and suggest a period of experimentation, perhaps all preparatory to the commissioning of the impressive entrance that was to be erected with the construction of the ramparts and ditches.p.63

Whilst the start of the earthwork phase must date to around 370 BC on archaeological grounds, the whole of the palisade phase needs to be placed before this to identify the start date of the settlement on the promontory. The palisaded phase of the site has only one generation of timber uprights used in the perimeter, and this was still standing when the gravel rampart west of the entrance was first built… It is thus suggested that settlement began on the promontory c.410 BC, with the palisade erected within a few years, and being is a state of decay by c.370 BC when the gravel rampart was constructed and some of the palisade was removed.pp.34–5

The northwestern entrance to the main promontory fort at Castell Henllys had a complex series of entrance gates during the palisade phase, and these were replaced with a stone entrance when the earthworks were constructed in Period 2 [c.370 BC]. The first stone phase comprised a double pair of semicircular guard chambers, together with massive timber uprights for the gate structures, and internal and external walling. All the walling was drystone construction, largely of shale quarried from the promontory slopes. The gateway was modified with posts replaced and added, and then it collapsed. At some point one part of the gateway suffered high temperature burning, creating slaggy material from the shale, equivalent to vitrification. The gateway collapsed, to be replaced by a second stone phase in Period 3 [c.280BC], with a single gate and one pair of shallow guard chambers, internal walling and external convex walling. In both periods there were also outer timber structures on the approach to the gate.p.231

The Period 3 stone northwestern gateway gradually collapsed, and along with unsuccessful attempts to stabilise the walls a timber gate was constructed on the rubble, and in the final phase of occupation there appears to have been no gate in this location.p.259

The ‘roundhouse’ is the classic Iron Age dwelling – generally between 5 and 15 metres in diameter, with wattle and daub walls. It is assumed that the walls would have been at least chest height, to allow maximum use of the enclosed space. Since the walls were round, the roof was conical, with a timber framework and a covering of thatch (or possibly turf, which, being heavier, would require more support). Often, the house’s entrance, which might have a porch, perhaps for reasons of belief rather than any purely practical consideration, faces south-east, towards the midwinter sunrise, or east, towards sunrise at the equinox.

iron04

The recent reinterpretation of the social significance of Iron Age houses has been closely related to the realization that roundhouse entrances were carefully and consciously oriented towards midwinter sunrise and the equinox, south-east and east respectively (Oswald 1997). Whilst these orientations had been noted by other archaeologists (Guilbert 1975), they had previously been interpreted as an attempt to compensate for strong western winds in the winter and to maximize sunlight in the interior (see also Pope 2007). Oswald (1997) undertook a detailed analysis of this issue that convincingly demonstrated these simplistic functionalist explanations would not have resulted in the very distinctive patterns observed in the archaeological record. Wind direction is affected by local topography and would create a much more generalized spread of orientations. Furthermore, there are major regional differences in the direction of bad weather between the east and west coast of Britain that should be visible in the archaeological record, if this was important in the construction of the house.Social Relations in Later Prehistory: Wessex in the first millennium BC (2010), Chapter 4 (pp.197–8). The works cited are: A. Oswald ‘A doorway on the past: practical and mystical concerns in the orientation of roundhouse doorways’, in Reconstructing Iron Age Societies: new approaches to the British Iron Age (1997); G.C. Guilbert ‘Planned Hillfort Interiors’, in Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society Vol. 41 (1975); R. Pope ‘Ritual and the roundhouse: a critique of recent ideas on domestic space in later British prehistory’, in The Earlier Iron Age in Britain and the Near Continent (2007).

At the centre of the house was an open-hearth fire, which would have been maintained at all times.[*] A bronze cauldron might be suspended from a tripod, by a chain, over the fire. The fire would have also enabled food to be preserved by drying and smoking. (Salt was also available to preserve meat.[*]) Spinning and weaving were domestic activities.[*]

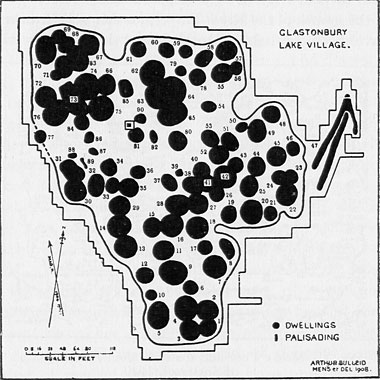

Glastonbury Lake Village was built, on an artificial island, in shallow water on the Somerset Levels. It was discovered, by Arthur Bulleid, in 1892. Excavations began in that year, and were completed in 1907.

iron05

On a Wednesday afternoon in March 1892, when driving from Glastonbury to Godney, a field was noticed to be covered with small mounds, an unusual feature in a neighbourhood where the conformation of the land is for miles at a dead level.Preliminary excavations demonstrated the site’s potential, but, because the trenches flooded, further investigation was postponed until summer:III. ‘The Discovery of the Somerset Lake-Villages’

Investigations were begun towards the end of July, 1892, and were continued each year from May to October until 1898, when there was an unavoidable interruption in the work for five years. Excavations were resumed again in the summer of 1904, when Mr H. ST GEORGE GRAY, F.S.A., happily joined the writer as a joint director and secretary of the work until its termination in 1907.After their work at the Glastonbury site, Bullied and Gray investigated a broadly contemporary site at nearby Meare. The settlements found at Glastonbury and Meare are often mentioned in the same breath, but they are quite different. While Glastonbury was constructed in a lake, Meare (which is actually two groups of houses, 60 metres apart) was built on a raised bog. At Meare there are clay floors and hearths, like Glastonbury, but unlike Glastonbury, there is very little superstructure remaining. This suggests that the houses were temporary affairs, like wigwams or tepees. Meare may have been a seasonal marketplace.III. ‘The Discovery of the Somerset Lake-Villages’

Since then, interpretations of the layers of archaeology that were uncovered have varied. It seems possible, however, that development of the village started around 250 BC. It peaked about 100 BC (a, roughly, triangular site of approximately 1.4 hectares, housing perhaps fourteen or fifteen extended families, some 200 people[*]), but rising water levels caused its abandonment about 50 BC. As a result of the waterlogged conditions, structural woodwork and wooden objects were very well preserved. The island’s foundations were made of brushwood and logs, filled in with rushes, bracken, peat and clay – the whole being retained by a perimeter palisade. On top, individual circular clay floors were laid as bases for roundhouses. The wall of a house was made by driving a circle of posts through the floor into the foundations (leaving a gap for the entrance of course). The spaces between these uprights were then filled with wattle and daub, and a thatched roof was erected. Arthur Bulleid writes:

Dwellings were occasionally burnt down, but there was no evidence of a great conflagration, nor of the total destruction of the Village by fire. It was in the locality of the burnt huts that information was forthcoming regarding the construction of the walls and roofs. The floors were thickly covered with baked clay rubble, charcoal, and pieces of charred reed. The pieces of baked clay were frequently marked with the impressions of wattle work on one side, and with finger-prints on the other. The fragments of charred reed were presumably burnt thatch. The roofs of the dwellings were supported by a central post, the base of which was usually found near the margin of the hearth embedded in the clay floor. Some of the larger dwellings appear to have had two or even more central posts. Other details of the construction are left largely to our imagination… From the complete hurdles that were discovered we conclude the walls were about six feet high, and some dwellings had partitions. Remains of flooring boards and joists were found in a few huts.The Lake-Villages of Somerset Fifth Edition (1958) §IV: E

As, over time, the foundations beneath a house compacted, so the floor would have to be built up again. In one instance a sequence of ten floors was found.

In dwelling-mounds with several floors, the superimposed layers of clay generally increased in diameter from below upwards. A new floor was usually accompanied by the re-erection of the dwelling, the diameter of the hut being increased.The Lake-Villages of Somerset Fifth Edition (1958) §IV: E

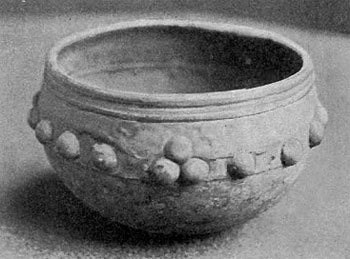

The roundhouses were between 5½ metres and 8½ metres in diameter. The entrances were not on any particular alignment. It seems that some houses must have had solid wooden doors (though none remained), since an iron latch-lifter and “a stone with a pivot-hole” were among the finds. In fact, a vast array of everyday objects were found in and around the village – items of bronze, tin, lead and iron; amber, glass, jet and shale; wood, bone and antler; pottery, baked-clay, flint and stone. Bronze-working and iron-working were carried out on the site. Of the 274 bronze items found, most were “objects of personal adornment”, though the prize find was a bowl.[*] Of the 18 tin objects, the most intriguing was a:

… round and solid bar of pure tin; it was capped at each end by a bronze terminal, and measured 10¼ inches in length, and one inch in diameter.The Lake-Villages of Somerset Fifth Edition (1958) Relics: I

Analysis of the bar’s surface suggested it had originally been gilded. There were 32 lead items, of which 13 were fishing-net sinkers. Of the 111 iron items, only 7 could be classed as weapons – “Daggers (including fragments) 3, spearheads 3, fragment of sword 1” – although:

That the inhabitants had iron weapons is certain, for numerous pieces of bronze bordering, and the terminals of three sheaths were discovered.The Lake-Villages of Somerset Fifth Edition (1958) Relics: I

There were parts of 4 snaffle-bits; and 4 saws – the teeth were set so that the cutting action was on the backward rather than, as in a modern handsaw, the forward stroke. Some of the iron tools still had their wooden handles.[*] 2 ‘currency bars’ were found, but just a single coin – an incomplete ‘potin’, dating from round-about 50 BC.

Five objects of amber and twenty-seven of glass were found, and with the exception of three glass specimens, all the objects were beads. A lump of greenish-blue glass slag is of much interest and importance, as it strongly supports the supposition that glass was made at the Village… Only one object was found made of jet, a highly polished ring or bead …The Lake-Villages of Somerset Fifth Edition (1958) Relics: III

The lathe was an Iron Age innovation, and objects of turned-wood and turned-shale were found at the Village.[*] There were 31 shale objects:

… these include two very fine lathe-turned and ornamented armlets. From the fact that a waste core was found, and several rings and other specimens in the process of making, we are led to believe that the shale was imported and worked at the village.The Lake-Villages of Somerset Fifth Edition (1958) Relics: IV

Amongst the “large collection” of wooden items were:

Portions of fourteen tubs and cups, either cut from the solid or stave-made. In some the staves were dowelled together, in others fitted together like a modern barrel and hooped. Sixty-three pieces of frame-work, parts of looms or apparatus for making textile fabrics. Five ladles, parts of three lathe-turned wheel-hubs, several wheel-spokes, a ladder with four steps, a small door … [handles from various tools] … fragments of baskets, two small wood pins found in association with a bronze mirror, tweezers and some dark colouring-matter, a draughtsman, the tops of two spade-handles, three pieces of finely ornamented wood bands, two wooden mallets, three stoppers, an oak dish or trough, beams and planks with mortise holes, and several wicker-made hurdles.The Lake-Villages of Somerset Fifth Edition (1958) Relics: V

A dugout canoe, of oak, was discovered by a labourer clearing the ditch of a nearby field. There were hundreds of bone and antler objects, including 89 weaving combs (counting fragments, and 5 which were not finished) and 5 dice. Three of the dice were found in association with 23 disc-shaped polished pebbles, which, presumably, were counters.

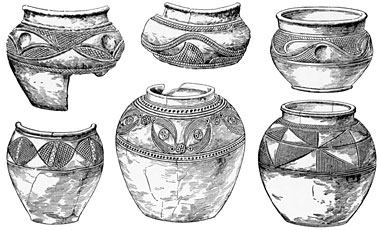

Although several tons weight of pot-sherds were unearthed only some half-a-dozen vessels were found intact… With reference to the production of the pottery, the clay and the other materials composing the various pastes were probably all products of the immediate neighbourhood, and there are reasons for thinking that the whole of the Glastonbury pottery was made at or near the village… With regard to the mechanism employed in making pottery, very few pots show any evidence of being wheel-made; the large bulk of the pottery was built up by hand.[*]The Lake-Villages of Somerset Fifth Edition (1958) Relics: X

Among the “very numerous” objects made of baked-clay were loom weights and spindle whorls, pieces of two tuyères (used to conduct the blast of air from bellows into the furnace), and hundreds of sling pellets. Most of the (in excess of 230) spindle whorls found at the Village were of stone. Also of stone, either whole or fragmentary, were 18 saddle quern components and 38 rotary quern components.[*] A Neolithic polished stone axe-head, and part of a second, were also discovered. These would not have been brought to the Village for practical use, but as curios or objects of reverence. There were also a few flint artifacts.

There is no actual proof that the fabrication of flint implements took place at the Village, but as the collection includes 362 flakes and chips, some of the latter being very small, we are led to believe that a flint industry was carried on, if for no other purpose than for the making of scrapers.The Lake-Villages of Somerset Fifth Edition (1958) Relics: XIV

Of course, living on an artificial island in a lake is not a concept unique to Somerset. In Scotland, loch-dwelling, on artificial islands called ‘crannogs’, has a history spanning thousands of years – from the 4th millennium BC, until at least the 17th century AD. It does appear, however, that the Iron Age and Roman period was the heyday of the crannog.[*] Typically, like at Glastonbury Lake Village, crannogs are true islands, having bases built up from the loch floor with organic material – brushwood, logs, peat, turf (perhaps augmented with stones) – retained by timber piling (a technique known as ‘packwerk’), but some loch-dwellers evidently lived in houses raised above the water on timber piles. These free-standing structures are also referred to as crannogs.

There are the remains of eighteen crannogs in Loch Tay alone. One of them, Oakbank Crannog, is a totally submerged mound, around 25 metres in diameter, that has been explored by underwater archaeologists since 1980. It is a multi-phase Iron Age site, but it seems it was originally constructed, around 500 BC, as a free-standing crannog – later, the collapsed structure becoming the basis of a packwerk-type mound, being overlaid with a layer of stones and a layer of large boulders.[*] Amongst the objects found in the debris of the collapsed house were: a wooden dish with butter sticking to it; a fragment of woven woolen cloth; a turned wooden disk (the waste removed from the base of a bowl once it has been taken off the lathe); an oak ard. Based on the findings at Oakbank, a reconstruction of a free-standing crannog was built in Loch Tay, some three miles east of Oakbank.

In the wild, rocky, landscape of ‘Atlantic Scotland’ (the north and west, including the Northern Isles and the Western Isles), drystone-walled roundhouses (today, called ‘Atlantic roundhouses’) began to be built around 800 BC. The early types, ‘simple Atlantic roundhouses’, had solid walls – sometimes quite massive: in the region of 4 metres thick. From about 400 BC, they began to acquire architectural features, such as galleries and stairways, within the thickness of the wall. These are classed as ‘complex Atlantic roundhouses’. Traditionally, Atlantic roundhouses are, in general, called ‘duns’ (the word dùn is Scottish Gaelic for ‘fortress’). Some are constructed on rocky-based artificial islands, and these are known as ‘island duns’. The imposing drystone towers, traditionally called ‘brochs’, fall under the heading of ‘complex Atlantic roundhouse’. Broch towers were probably fully developed by about 200 BC.

iron06

The earliest evidence for the construction of thick-walled drystone roundhouses comes from Orkney … Dating from c.800 to 400 BC these sites represent a clear departure in terms of scale and external appearance from the stone-built forms of the Late Bronze Age while they foreshadow the development of more complex stone roundhouses incorporating galleries and cells within their walls. The massively built roundhouse at Bu on Orkney is usually taken to be the type site of this simple form of Atlantic roundhouse (Hedges 1987)… The construction of more complex Atlantic roundhouse forms appears to have begun in the north from c.400 BC onwards (Gilmour 2002; Armit 2003)… The appearance of fully formed complex roundhouse towers, exemplified by well-preserved sites such as Mousa in Shetland, cannot be dated to before 200 BC in the Northern Isles or indeed anywhere else in Atlantic Scotland. For example, complex roundhouses built sometime prior to the second century BC at Crosskirk and the Howe do not appear to have been built substantially enough to support tower constructions higher than 4.5m, which is around half the height of later complex towers (Armit 2003).The Atlantic Iron Age: Settlement and identity in the first millennium BC (2007), Chapter 5 (p.154–6). The works cited are: J.W. Hedges Bu, Gurness and the Brochs of Orkney Vols. 1-3 (1987); S. Gilmour ‘Mid-first millennium BC settlement in the Atlantic West?’, in In the Shadow of the Brochs: The Iron Age in Scotland, (2002); I. Armit Towers in the North: The Brochs of Scotland (2003).

The towers are entered by a single, low, doorway and have no windows. This somewhat featureless exterior, combined with the slope of the wall, has led to them being likened to power station cooling towers. The entrance passage usually has a, so called, ‘guard-cell’ to one side, within the wall’s thickness. Presumably (though not proven), the towers would have had a number of wooden upper floors and a conical roof – certainly, typical features of ‘broch architecture’ are ‘scarcements’, i.e. stone ledges, around the inside of the tower which could have provided support for an internal timber structure. The name ‘broch’ is derived from the Old Norse borg, i.e. ‘fortress’, and these substantial towers would, no doubt, act as a stronghold when raiding parties attacked. They are, however, very prominent in the landscape. They were, clearly, built to be impressive. It does not seem unreasonable to see them as status symbols – blatantly advertising the wealth of the family who lived there. Their heyday would appear to span four hundred years, the last two centuries BC and the first two AD.

Broadly contemporary with the broch towers, and found in the Western Isles (mainly) and Shetland (but not Orkney), is a completely different class of circular drystone building: the ‘wheelhouse’ – named from its distinctive floorplan.[*] Arranged radially around the interior, like wheel spokes, are a number of stone piers. The central hub area is left open. The wall and piers supported corbelled stone roofs, which domed above each of the inter-spoke cells. At Cnip, on Lewis (Western Isles), the corbelled roofing of a wheelhouse is partially intact. The domes’ apexes would have been something like 6 metres above floor level. Whereas brochs probably made lavish use of timber, in an area where its supply was very limited, wheelhouses only required timber to construct the framework of a roof over the hub area. The example at Cnip had an interior diameter of 7 metres, eight spokes, and the hub diameter was in the region of only 3½ metres. An example at Sollas, on North Uist (Western Isles) was 11 metres in diameter, had 13 spokes, and a 7 metre hub diameter. Frequently, wheelhouses are sunk into machair (sand-based grassland), so don’t need massive walls to hold them up – Cnip and Sollas are both like this. Only the roofs would have projected above the land surface.

Of course, not all the “dwellings” shown on Arthur Bulleid’s plan were in existence at the same time, nor would they have all been domestic quarters. According to Arthur Bulleid*, “evidence of occupation in about twenty was very scanty”. The limb to the east of the village is a causeway/landing stage arrangement. The wetness of the village’s surroundings would have varied with the seasons – perhaps around a metre of standing water in the winter, but maybe little more than quagmire in the summer.

*

Of course, not all the “dwellings” shown on Arthur Bulleid’s plan were in existence at the same time, nor would they have all been domestic quarters. According to Arthur Bulleid*, “evidence of occupation in about twenty was very scanty”. The limb to the east of the village is a causeway/landing stage arrangement. The wetness of the village’s surroundings would have varied with the seasons – perhaps around a metre of standing water in the winter, but maybe little more than quagmire in the summer.

*  The Glastonbury Bowl (about 11½cm diameter, 8cm deep) is made from two bronze-sheet sections riveted together. Presumably the original top section was damaged, since the present one would appear to be a replacement. The bowl, along with a great many other finds, was unearthed immediately outside the perimeter palisade. Of course, some items may have simply been dropped accidentally, others dumped as rubbish, but it seems reasonable to suppose that many, the bowl included, were purposely committed to the water as votive offerings.

The Glastonbury Bowl, and other finds from the Village, are on display in

The Glastonbury Bowl (about 11½cm diameter, 8cm deep) is made from two bronze-sheet sections riveted together. Presumably the original top section was damaged, since the present one would appear to be a replacement. The bowl, along with a great many other finds, was unearthed immediately outside the perimeter palisade. Of course, some items may have simply been dropped accidentally, others dumped as rubbish, but it seems reasonable to suppose that many, the bowl included, were purposely committed to the water as votive offerings.

The Glastonbury Bowl, and other finds from the Village, are on display in

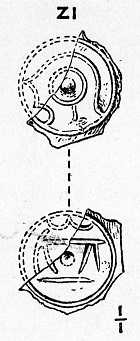

It would appear from the illustration of the potin fragment found at Glastonbury Lake Village, published by Arthur Bulleid and his co-worker, Harold St George Gray, in 1917 (the fragment itself is now missing), that it was of similar type to the one in the photo. Dating these early coins is far from being an exact science, but according to a scheme proposed by Colin C. Haselgrove* this type post-dates 60 BC.

* ‘Potin Coinage in Iron Age Britain, Archaeology and Chronology’ (Gallia Tome 52, 1995), freely available

It would appear from the illustration of the potin fragment found at Glastonbury Lake Village, published by Arthur Bulleid and his co-worker, Harold St George Gray, in 1917 (the fragment itself is now missing), that it was of similar type to the one in the photo. Dating these early coins is far from being an exact science, but according to a scheme proposed by Colin C. Haselgrove* this type post-dates 60 BC.

* ‘Potin Coinage in Iron Age Britain, Archaeology and Chronology’ (Gallia Tome 52, 1995), freely available

The ard, or ‘scratch plough’, doesn’t cut and turn the soil, but simply gouges the surface. To obtain a good tilth, a field was ploughed in one direction and then cross-ploughed in the other. The ard found at Oakbank (above) is a single piece of oak. At the business end of the ard (left in the photo) is a tang, which could have held a ‘share’ made of iron. The introduction of the iron share allowed heavier soils to be cultivated.

The ard, or ‘scratch plough’, doesn’t cut and turn the soil, but simply gouges the surface. To obtain a good tilth, a field was ploughed in one direction and then cross-ploughed in the other. The ard found at Oakbank (above) is a single piece of oak. At the business end of the ard (left in the photo) is a tang, which could have held a ‘share’ made of iron. The introduction of the iron share allowed heavier soils to be cultivated.