SUPPLEMENT

Addenda to Times Change

IRON

It was not possible to get high enough furnace temperatures to release liquid iron from its ore. After smelting, an iron ‘bloom’ was left. This spongy mass was subjected to a protracted session of heating and hammering (by a ‘bloomsmith’), to force out as much of the remaining impurity (‘slag’) as possible, producing ‘wrought iron’. Since the temperatures enabling iron to be cast were not available, all iron artifacts were manufactured by reheating and hammering (by a ‘blacksmith’). Pure wrought iron is relatively soft, but it can be hardened by alloying it with another element. Some alloys form naturally because the ore contains suitable impurities.

There are numerous varieties of iron; the first difference depending on the kind of soil or of climate – some lands only yield a soft iron closely allied to lead, others a brittle and coppery kind that is specially to be avoided for the requirements of wheels and for nails, for which purpose the former quality is suitable; another variety of iron finds favour in short lengths only and in nails for soldiers’ boots; another variety experiences rust more quickly.Pliny the Elder (AD 23–AD 79) Natural History XXXIV, 41

Steel is produced by alloying iron with carbon. By a process called ‘carburisation’ – heating iron with carbon, i.e. charcoal, for a long period, allowing carbon to diffuse into the iron’s surface – it is possible to produce a steel coating to give a sword a harder cutting edge. The properties of the metal can be further modified by ‘quenching’ (the heated metal is rapidly cooled by plunging into a liquid), which increases hardness, but with the penalty of increasing brittleness too,[*] and ‘tempering’ (the heated metal is allowed to cool gradually), which reverses the action of quenching (the hotter the metal was to start with, the softer it is when cooled). By judiciously combining these operations, the hardness of the final product can be finely tuned. For most purposes, however, wrought iron was perfectly satisfactory.

Relatively few artefacts show evidence for advanced techniques like the deliberate use of steel, or even quenching and tempering, but smiths gradually learned enough about the properties of different ores to choose those best suited for particular tasks …Charles Haselgrove: ‘The Iron Age’, The Archaeology of Britain Second Edition (2009),

Chapter 7 (p.163).

Obviously, smiths of the period did not have a scientific understanding of the processes they were using, and the quality of the end product would appear to have been somewhat variable. In 367 BC, Marcus Furius Camillus, at almost eighty years of age, defeated an army of Gauls who were marching on Rome. Plutarch (c.AD 45–c.AD 120), in his biography of Camillus, writes:

Finally, when Camillus led his men-at-arms to the attack, the enemy raised their swords on high and rushed for close quarters. But the Romans thrust their javelins into their faces, received their strokes on the parts that were shielded by iron, and so turned the edge of their metal, which was soft and weakly tempered, so much so that their swords quickly bent up double, while their shields were pierced and weighed down by the javelins which stuck in them.Parallel Lives ‘Camillus’ 41

Polybius (c.200 BC–c.118 BC) records a victory achieved by the Romans over the Gauls in 223 BC:

The Romans are thought to have managed matters very skilfully in this battle, their tribunes having instructed them how they should fight, both as individuals and collectively. For they had observed from former battles that Gauls in general are most formidable and spirited in their first onslaught, while still fresh, and that, from the way their swords are made, as has been already explained,[*] only the first cut takes effect; after this they at once assume the shape of a strigil, being so much bent both length-wise and side-wise that unless the men are given leisure to rest them on the ground and set them straight with the foot, the second blow is quite ineffectual.[*] The tribunes therefore distributed among the front lines the spears of the triarii who were stationed behind them, ordering them to use their swords instead only after the spears were done with. They then drew up opposite the Celts in order of battle and engaged. Upon the Gauls slashing first at the spears and making their swords unserviceable the Romans came to close quarters, having rendered the enemy helpless by depriving them of the power of raising their hands and cutting, which is the peculiar and only stroke of the Gauls, as their swords have no points. The Romans, on the contrary, instead of slashing continued to thrust with their swords which did not bend, the points being very effective. Thus, striking one blow after another on the breast or face, they slew the greater part of their adversaries.The Histories II, 33

Translations:

Polybius The Histories by W.R. Paton

Plutarch Parallel Lives by Bernadotte Perrin

Pliny the Elder Natural History by H. Rackham

THE FALL OF MAIDEN CASTLE

Sir Mortimer Wheeler’s description of the fall of Maiden Castle:

And so we reach the Roman invasion of A.D. 43. That part of the army of conquest wherewith we are concerned in Dorset had as its nucleus the Second Augustan Legion, whose commander, at any rate in the earlier campaigns, was the future Emperor Vespasian. Precisely how soon the invaders reached Maiden Castle can only be guessed, but by A.D. 47 the Roman arms had reached the Severn, and Dorset must already have been overrun. Suetonius affirms that Vespasian reduced “two very formidable tribes and over twenty towns (oppida), together with the Isle of Wight”, and it cannot be doubted that, whether or no the Durotriges (as is likely enough) were one of the tribes in question, the conquest of the Wessex hill-fort system is implied in the general statement. Nor is it improbable that, with the hints provided by the mention of the Isle of Wight and by the archaeological evidence for the subsequent presence of the Second Legion near Seaton in eastern Devon, a main line of advance lay through Dorset roughly along the route subsequently followed by the Roman road to Exeter. From that road today the traveller regards the terraced ramparts of the western entrance of Maiden Castle; and it requires no great effort of the imagination to conjure up the ghost of Vespasian himself, here confronted with the greatest of his “twenty towns”.[*] Indeed, something less than imagination is now required to reconstruct the main sequence of events at the storming of Maiden Castle, for the excavation of the eastern entrance has yielded tangible evidence of it. With only a little amplification it may be reconstructed as follows.

Approaching from the direction of the Isle of Wight, Vespasian’s legion may be supposed to have crossed the River Frome at the only easy crossing hereabouts – where Roman and modern Dorchester were subsequently to come into being. Before the advancing troops, some 2 miles away, the sevenfold ramparts of the western gates of Dunium towered above the cornfields which probably swept, like their modern successors, up to the fringe of the defences. Whether any sort of assault was attempted upon these gates we do not at present know; their excessive strength makes it more likely that, leaving a guard upon them, Vespasian moved his main attack to the somewhat less formidable eastern end. What happened there is plain to read. First, the regiment of artillery, which normally accompanied a legion on campaign, was ordered into action, and put down a barrage of iron-shod ballista-arrows over the eastern part of the site. —

— Following this barrage, the infantry advanced up the slope, cutting its way from rampart to rampart, tower to tower. In the innermost bay of the entrance, close outside the actual gates, a number of huts had recently been built; these were now set alight, and under the rising clouds of smoke the gates were stormed and the position carried. —

— But resistance had been obstinate and the fury of the attackers was roused. For a space, confusion and massacre dominated the scene. Men and women, young and old, were savagely cut down, before the legionaries were called to heel and the work of systematic destruction began. That work included the uprooting of some at least of the timbers which revetted the fighting-platform on the summit of the main rampart; but above all it consisted of the demolition of the gates and the overthrow of the high stone walls which flanked the two portals. The walls were now reduced to the lowly and ruinous state in which they were discovered by the excavator nearly nineteen centuries later.

That night, when the fires of the legion shone out (we may imagine) in orderly lines across the valley, the survivors crept forth from their broken stronghold and, in the darkness, buried their dead as nearly as might be outside their tumbled gates, in that place where the ashes of their burned huts lay warm and thick upon the ground. The task was carried out anxiously and hastily and without order, but, even so, from few graves were omitted those tributes of food and drink which were the proper and traditional perquisites of the dead. —

— At daylight on the morrow, the legion moved westward to fresh conquest, doubtless taking with it the usual levy of hostages from the vanquished.

Thereafter, salving what they could of their crops and herds, the disarmed townsfolk made shift to put their house in order. Forbidden to refortify their gates, they built new roadways across the sprawling ruins, between gateless ramparts that were already fast assuming the blunted profiles that are theirs today. And so, for some two decades, a demilitarized Maiden Castle retained its inhabitants, or at least a nucleus of them. Just so long did it take the Roman authorities to adjust the old order to the new, to prepare new towns for old. And then finally, on some day towards the close of the sixties of the century, the town was ceremonially abandoned, its remaining walls were formally ‘slighted’, and Maiden Castle lapsed into the landscape among the farm-lands of Roman Dorchester.Maiden Castle, Dorset I, 16

Published by the Society of Antiquaries of London (1943), freely available online.

Sir Mortimer’s interpretation is very compelling, but a more recent interpretation suggests that Maiden Castle’s abandonment followed a protracted decline rather than a sudden catastrophic assault. Niall Sharples (in a compendium entitled The Celts, from 1991) writes:

During the second century B.C. Maiden Castle is at its most impressive. Work on the defences has been completed and the interior is fully occupied. Circular houses are arranged in rows to create streets and large areas are given over to grain storage in underground silos. In this form Maiden Castle is not only the largest but the most elaborately defended and most densely occupied hillfort in southern England. The construction and reconstruction of the ramparts would have involved large numbers of people and could not have been carried out solely by the inhabitants of the fort. Likewise the grain storage facilities are too substantial to be solely for the use of the inhabitants. It is not unreasonable, therefore, to suggest that this was the capital of a large territory, perhaps as large as the present county of Dorset.

In the succeeding centuries the significance of the hillfort seems to have diminished. There is evidence that the ramparts became neglected and much of the interior was abandoned. The bulk of the inhabitants appear to have moved back into small settlements scattered around the hillfort. These settlements were associated with their own fields and paddocks and it seems likely that there was a movement away from communal farming controlled from the hillfort to individual autonomous farms. The hillfort must have retained some preeminence in the community, however, as in the abandoned earthworks of the eastern entrance there is one of the largest and richest cemeteries known from southern England in this period. Several hundred burials are likely to be present and many individuals have elaborate grave goods indicating their status and role in the community. These offerings include pots, presumably containing food and drink, joints of animals, weapons and ornaments.

Amongst these burials are a group of individuals who show signs of violent death. Several have sword cuts across the skull and principal limbs, one has the clear impression of a spearhead which has pierced the skull and another has a spear actually embedded into his backbone. These burials testify to the violent nature of Celtic society in the late Iron Age of the British Isles and it is possible that they result from a vain attempt to impede the Roman occupation of southern England in A.D. 43. The hillfort was abandoned within fifty years of the invasion and other than a short period in the fourth and fifth centuries, when it was the site of a Romano-Celtic temple, it has remained unoccupied since then.‘Maiden Castle, Dorset, Britain’ (p.607)

Hod Hill, another Dorset hillfort (at almost 22 hectares, Hod Hill has a greater enclosed area than Maiden Castle), was excavated in the 1950s by Sir Ian Richmond. Eleven iron ballista bolts were found clustered around, what was taken to be, a “chieftain’s hut” (a roundhouse set within a, rectangular, ditched enclosure), near the south-eastern corner of the interior. The interpretation was, once again, that this was evidence of a Roman assault on the hillfort, though there are no other signs of a fight. Anyway, the Roman military appropriated the hillfort, and built their own fort in the north-western corner – making use of the existing ramparts to provide its northern and western defences.[*] Dave Stewart and Miles Russell, in Current Archaeology (Issue 336, March 2018), write:

At Hod Hill, the ballista bolts found during Ian Richmond’s excavation could easily (and more plausibly) have come from the Roman fort, where catapult foundation platforms were discovered; it is quite probable that they could have been discharged during target practice rather than in some speculative attack. Crucially, archaeological evidence also suggests that both Maiden Castle and Hod Hill had been largely abandoned by 100 BC, a century and a half before the Romans arrived.[*]

Nevertheless, Suetonius does say that Vespasian fought thirty battles, and had to overcome more than twenty oppida – which can only be hillforts.[*] It does not seem unreasonable to suppose that groups of British warriors would choose to make their last-stands in these strategically sited, if rather run-down, fortifications.

OPPIDA

It was Julius Caesar who first referred to major Gallic and British tribal settlements/strongholds as oppida (singular: oppidum). The term has been pressed into service by archaeologists.

By about 100 BC, whilst hillforts tended to be in a state of decline, in south-eastern Britain a new type of settlement, called ‘enclosed oppida’ by archaeologists, emerged. River valleys are the favoured location for enclosed oppida. They cover areas in excess of 10 hectares, and are bounded by earthworks – or partially bounded: natural landscape features are often employed to complete the boundary. For instance, at Dyke Hills, Oxfordshire, an area of about 45 hectares is enclosed on the west and south by a loop of the river Thames; on the east by the river Thame; and on the north by a linear earthwork comprising two banks with broad intervening ditch. The enclosed oppida appear to represent the last gasp of, what might be termed, the ‘hillfort concept’ in the south-east.

By the turn of the millennium the, so-called, ‘territorial oppida’ appear, where large areas of land are defined by discontinuous lengths of earthwork. At Camulodunum (Colchester, Essex), the defined territory covers about 30 square kilometres. After the Conquest, a Roman town was built within this area. The same thing happened in the territorial oppida of Calleva (Silchester, Sussex), Verulamium (St Albans, Hertfordshire) and Durovernum (Canterbury, Kent). Though these oppida had clearly been important tribal centres, it is only at Silchester that any evidence of what could be a pre-Roman town – two roads, at right angles, with plots at right angles to them, dated c.15 BC – has, as yet, been uncovered.

Addenda to First Contacts

BRITANNIAE

Unlike the modern concept of ‘the British Isles’, Britanniae, translated along the lines of ‘the Britains’, ‘the Britannias’ or ‘the Britannic Islands’, refers to all islands off the north-western coast of mainland Europe. For instance, Pliny the Elder (AD 23–AD 79), discussing Britanniae, notes:

… scattered about in the direction of the German Sea, are the Glass Islands [Glaesariae], which the Greeks in more modern times have called the Electrides, because amber [Greek: elektron] is produced there. —

— The most remote of all those recorded is Thule, in which as we have pointed out there are no nights at midsummer when the sun is passing through the sign of Cancer, and on the other hand no days at midwinter; some writers think this is the case for periods of six months at a time without a break.Natural History IV, 16

Pytheas of Massalia writes that this occurs in the island of Thule, six days’ voyage north from Britain,Natural History II, 77

One day’s sail from Thule is the frozen ocean, called by some the Cronian Sea.Natural History IV, 16

Whilst Pliny is happy to accept Pytheas as a credible witness, Polybius (c.200 BC–c.118 BC) evidently thought Pytheas was a charlatan. The section of The Histories in which he criticises Pytheas is now lost, but Polybius’ incredulity has been preserved by Strabo (c.64 BC–c.AD 24):

Polybius, in his account of the geography of Europe, says he passes over the ancient geographers but examines the men who criticise them, namely, Dicaearchus, and Eratosthenes, who has written the most recent treatise on Geography; and Pytheas, by whom many have been misled; for after asserting that he travelled over the whole of Britain that was accessible Pytheas reported that the coast-line of the island was more than forty thousand stadia,[*] and added his story about Thule and about those regions in which there was no longer either land properly so-called, or sea, or air, but a kind of substance concreted from all these elements, resembling a sea-lung – a thing in which, he says, the earth, the sea, and all the elements are held in suspension; and this is a sort of bond to hold all together, which you can neither walk nor sail upon. Now, as for this thing that resembles the sea-lung, he says that he saw it himself, but that all the rest he tells from hearsay…

Now Polybius says that, in the first place, it is incredible that a private individual – and a poor man too – could have travelled such distances by sea and by land … Pytheas asserts that he explored in person the whole northern region of Europe as far as the ends of the world – an assertion which no man would believe, not even if Hermes made it.Geography II, 4.1–2

Perhaps it was a combination of professional jealousy and snobbery that inspired Polybius’ snide remarks – after all he was a Greek aristocrat (from Megalopolis, Arcadia), whilst Pytheas was just “a poor man”. Strabo (a Greek from Amaseia – now Amasya, in Turkey), who, in all probability, had only come across Pytheas’ work in secondary sources, heartily agreed with Polybius’ assessment of Pytheas. It becomes clear, though, that this is because Pytheas’ reports clashed with Strabo’s preconceived geographical notions.

Translations:

Strabo Geography by Horace Leonard Jones

Pliny the Elder Natural History adapted from the translation of H. Rackham

STRABO’S GEOGRAPHY

As previously mentioned, Strabo claimed Pytheas was a liar:

For not only has the man who tells about Thule, Pytheas, been found, upon scrutiny, to be an arch-falsifier, but the men who have seen Britain and Ierne [Ireland] do not mention Thule, though they speak of other islands, small ones, about Britain …Geography I, 4.3

Strabo was writing, probably in Rome, some three centuries after Pytheas. (Allusions in the Geography suggest it was completed in, or just after, AD 23, though the timescale of its production is the subject of debate.) Whilst Strabo was a lad, Julius Caesar had brought all Gaul under Roman control, and made two expeditions to Britain (in 55 BC and 54 BC). Caesar, himself, wrote:

The island is triangular in its shape, one side being opposite Gaul. One corner of this side, by Kent – the landing-place for almost all ships from Gaul – has an easterly, and the lower one a southerly aspect. The extent of this side is about 500 [Roman] miles. The second tends westward towards Spain: off the coast here is Ireland, which is considered only half as large as Britain, though the passage is equal in length to that between Britain and Gaul. Halfway across is an island called Mona; and several smaller islands also are believed to be situated opposite this coast, in which, according to some writers, there is continuous night, about the winter solstice, for 30 days. Our inquiries could elicit no information on the subject, but by accurate measurements with a water-clock we could see that the nights were shorter than on the continent. The length of this side, according to the estimate of the natives, is 700 miles. The third side has a northerly aspect, and no land lies opposite it; its corner, however, looks, if anything, in the direction of Germany. This length of this side is estimated at 800 miles. Thus the whole island is two thousand miles in circumference.The Gallic War V, 13

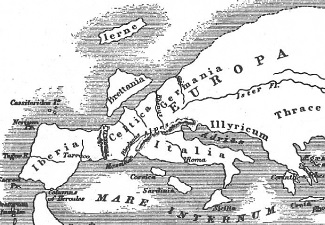

Caesar’s idea that the west coast of Britain faced towards Spain seems bizarre today [Map]. He appears to have come to this conclusion by imagining that the coast of Gaul ran in a virtually straight line from the Rhine to the Pyrenees:

… the whole of Gaul having a northerly trend …The Gallic War IV, 20

Such a ‘flattening’ of Gaul would, in effect, rotate the British Isles towards Spain. It seems reasonable to assume that, by the time Strabo wrote his Geography, the coastlines of Gaul and southern Britain would have become familiar to the Romans. It would, therefore, seem reasonable to expect Strabo’s description to be an advance on Caesar’s. That, however, is not the case. Instead, Strabo (who never travelled west of Italy) developed his own, curious, notion of the area’s geography:

Next to Iberia towards the east lies Celtica [Gaul], which extends to the River Rhine. On its northern side it is washed by the whole British Channel (for the whole island of Britain lies over against and parallel to the whole of Celtica and stretches lengthwise about five thousand stadia) …Geography, II, 5.28

Britain is triangular in shape; and its longest side stretches parallel to Celtica, neither exceeding nor falling short of the length of Celtica …Geography IV, 5.1

… Britain itself stretches alongside of Celtica with a length about equal thereto, being not greater in length than five thousand stadia, and its limits are defined by the extremities of Celtica which lie opposite its own. For the eastern extremity of the one country lies opposite the eastern extremity of the other, and the western extremity of the one opposite the western of the other; and their eastern extremities, at all events, are near enough to each other for a person to see across from one to the other – I mean Kent and the mouths of the Rhine. But Pytheas declares that the length of Britain is more than twenty thousand stadia, and that Kent is several days’ sail from Celtica …Geography I, 4.3

As demonstrated by Diodorus’ record, Pytheas had described Britain as triangular in shape, but had correctly identified the side adjacent to Gaul as the shortest (giving it a length of 7,500 stadia). Pytheas did indeed say the longest side was 20,000 stadia, but this was the western coast. Strabo might appear to have a valid point when he queries a journey of “several days” from Gaul to Kent. However, in the real world, Pytheas had to round the Armorican peninsula (Brittany). A journey from there, diagonally across the Channel to Kent, would have taken days. Strabo was, clearly, totally convinced that his vision of Europe was correct, and that Pytheas was lying.

… any man who has told such great falsehoods about the known regions would hardly, I imagine, be able to tell the truth about places that are not known to anybody.Geography I, 4.3

When Strabo talks of “places that are not known to anybody”, he is talking about Thule.

Now Pytheas of Massalia tells us that Thule, the most northerly of the Britannic Islands, is farthest north, and that there the circle of the summer tropic is the same as the arctic circle. But from the other writers I learn nothing on the subject – neither that there exists a certain island by the name of Thule, nor whether the northern regions are inhabitable up to the point where the summer tropic becomes the arctic circle. But in my opinion the northern limit of the inhabited world is much farther to the south than where the summer tropic becomes the arctic circle. For modern scientific writers are not able to speak of any country north of Ierne [Ireland], which lies to the north of Britain and near thereto, and is the home of men who are complete savages and lead a miserable existence because of the cold; and therefore, in my opinion, the northern limit of our inhabited world is to be placed there.Geography II, 5.8

Translations:

Strabo Geography by Horace Leonard Jones

Julius Caesar The Gallic War by T. Rice Holmes

SIMILARITIES

The similarity between Diodorus’ note on harvesting and one in the following passage by Strabo, indicates that Diodorus’ information originated with Pytheas:

Concerning Thule our historical information is still more uncertain, on account of its outside position; for Thule, of all the countries that are named, is set farthest north. But that the things which Pytheas has told about Thule, as well as the other places in that part of the world, have indeed been fabricated by him, we have clear evidence from the districts that are known to us, for in most cases he has falsified them, as I have already said before, and hence he is obviously more false concerning the districts which have been placed outside the inhabited world. And yet, if judged by the science of the celestial phenomena and by mathematical theory, he might possibly seem to have made adequate use of the facts as regards the people who live close to the frozen zone, when he says that, of the animals and domesticated fruits, there is an utter dearth of some and a scarcity of the others, and that the people live on millet and other herbs, and on fruits and roots; and where there are grain and honey, the people get their beverage, also, from them. As for the grain, he says – since they have no pure sunshine – they pound it out in large storehouses, after first gathering in the ears thither; for the threshing floors become useless because of this lack of sunshine and because of the rains.Geography IV, 5.5 (Translation by Horace Leonard Jones.)

ICTIS, THE TIN TRADE, AND THE VENETI

The inhabitants of Britain who dwell about the promontory known as Belerion are especially hospitable to strangers and have adopted a civilized manner of life because of their intercourse with merchants of other peoples… they work the tin into pieces the size of knuckle-bones and convey it to an island which lies off Britain and is called Ictis; for at the time of ebb-tide the space between this island and the mainland becomes dry and they can take the tin in large quantities over to the island on their wagons… On the island of Ictis the merchants purchase the tin of the natives and carry it from there across the Strait to Gaul …Diodorus Siculus: Library of History V, 22

The most popular contender for the island of Ictis is St Michael’s Mount, off the coast of the Penwith peninsula of Cornwall. This matches the geographical description perfectly, but, as yet, no evidence of the tin trade has been discovered. Another plausible candidate is Mount Batten, in Plymouth Sound. This has indisputable evidence of trading activity, but, at the present time anyway, is permanently attached to the mainland.

Pliny the Elder notes that:

The historian Timaeus says there is an island named Mictis lying inward six days’ sail from Britain where tin is found, and to which the Britons cross in boats of osier covered with stitched hides.Natural History IV, 16

It is not clear whether this island of Mictis should be equated with Diodorus’ island of Ictis. Pliny’s statement is somewhat ambiguous (is it Britain, generally, or Mictis, in particular, where tin is found), and, clearly, Diodorus’ Ictis was not a six day sail from the immediate mainland. Possibly Mictis was a completely different island, or perhaps Pliny’s story is basically the same as Diodorus’, but presented in a garbled form.

By the time of Julius Caesar’s campaigns in Gaul (58–51 BC), the tribe inhabiting the southern coast of the Breton peninsula were called the Veneti. In The Gallic War, Caesar, himself, notes that the Veneti were:

… by far the most influential of all maritime peoples in that part of the country. They possess numerous ships, in which they regularly sail to Britain; they excel the other peoples in knowledge of navigation and in seamanship; and, the sea being very stormy and open, with only a few scattered harbours, which they keep under their control, they compel almost all who sail those waters to pay toll.The Gallic War III, 8

Presumably, these same people (though perhaps differently named) were engaged in the cross-Channel tin trade at the time of Pytheas. Their ships, which are described by Caesar, probably hadn’t changed substantially, either, in the intervening years.

They were a good deal more flat-bottomed than ours, to adapt them to the conditions of shallow water and ebbing tides. Bows and sterns alike were very lofty, being thus enabled to resist heavy seas and severe gales. The hulls were built throughout of oak, in order to stand any amount of violence and rough usage. The cross-timbers, consisting of beams a foot thick, were riveted with iron bolts as thick as a man’s thumb. The anchors were secured with iron chains instead of ropes. Hides or leather dressed fine were used instead of sails, either because flax was scarce and the natives did not know how to manufacture it [i.e. linen], or, more probably, because they thought it difficult to make head against the violent storms and squalls of the Ocean, and to manage vessels of such burthen with ordinary sails.The Gallic War III, 13

By the onset of winter in 57 BC, Caesar believed that Gaul had been subdued. The Veneti, however, initiated a rebellion. Caesar responded by ordering that a fleet of warships be built, on the River Loire. Caesar notes that the Veneti:

… sent for reinforcements to Britain, which faces that part of Gaul.The Gallic War III, 9

In late-summer, 56 BC, the Veneti’s rebellion climaxed in a sea-battle.

To backtrack a little. Caesar says (The Gallic War II, 34) that it was one Publius Crassus, at the head of a legion, who secured the submission of the Veneti, and their neighbouring “maritime tribes”, in 57 BC. Strabo (Geography III, 5.11) reports that a Publius Crassus voyaged to a group of tin-producing islands called the Cassiterides. Strabo places these islands to the north of Iberia, and gives quite a detailed description of them, but they have never been satisfactorily identified, and they may well be mythical.

i_a_n01

… I have no reliable information to pass on about the western margins of Europe, because I at any rate do not accept that there is a river which the natives there call the Eridanus (said to issue into the northern sea and to be the source of amber), and I am not certain that the Cassiterides exist, which are supposed to be the source of our tin. In the first place, the very name ‘Eridanus’ tells against its existence, because it is not a foreign word, but Greek, made up by some poet. In the second place, despite my efforts, I have been unable to find anyone who has personally seen a sea on the other side of Europe and can tell me about it. Nevertheless, it is true that our tin and our amber come from the outermost reaches of the world.Pliny the Elder (AD 23–AD 79):Histories III, 115

Opposite to Celtiberia are a number of islands called by the Greeks the Tin Islands [Cassiterides] in consequence of their abundance of that metal …Natural History IV, 22

The next topic is the nature of lead, of which there are two kinds, black and white. White lead [tin] is the most valuable; the Greeks applied to it the name cassiteros, and there was a legendary story of their going to islands of the Atlantic ocean to fetch it and importing it in platted vessels made of osiers and covered with stitched hides.Strabo (c.64 BC–c.AD 24):Natural History XXXIV, 47

The Cassiterides are ten in number, and they lie near each other in the high sea to the north of the port of the Artabrians [i.e. the northwest corner of Iberia]. One of them is desert, but the rest are inhabited by people who wear black cloaks, go clad in tunics that reach to their feet, wear belts around their breasts, walk around with canes, and resemble the goddesses of Vengeance in tragedies. They live off their herds, leading for the most part a nomadic life. As they have mines of tin and lead, they give these metals and the hides from their cattle to the sea-traders in exchange for pottery, salt and copper utensils. Now in former times it was the Phoenicians alone who carried on this commerce (that is, from Gades [Cadiz]), for they kept the voyage hidden from every one else. And when once the Romans were closely following a certain ship-captain in order that they too might learn the markets in question, out of jealousy the ship-captain purposely drove his ship out of its course into shoal water; and after he had lured the followers into the same ruin, he himself escaped by a piece of wreckage and received from the State the value of the cargo he had lost. Still, by trying many times, the Romans learned all about the voyage. After Publius Crassus crossed over to these people and saw that the metals were being dug from only a slight depth, and that the men there were peaceable, he forthwith laid abundant information before all who wished to traffic over this sea, albeit a wider sea than that which separates Britain from the continent. So much, then, for Iberia and the islands that lie off its coast.Geography III, 5.11

Now, it doesn't seem like much of a leap to identify Strabo’s voyager Publius Crassus with Caesar’s Publius Crassus (though there was an earlier Publius Crassus, who served in Iberia in the 90s BC). Perhaps, then, it was actually Cornwall that Crassus visited, on a Veneti ship, in 57 BC. Strabo also mentions:

… the Veneti who fought the naval battle with Caesar; for they were already prepared to hinder his voyage to Britain, since they were using the emporium there.Geography IV, 4.1

In which case, it would appear that the prospect of having their lucrative business ruined if Caesar crossed the Channel prompted the Veneti to instigate the rebellion.

It was probably in Quiberon Bay that Caesar’s fleet (its size is not mentioned) was met by an armada of “about 220” Veneti ships.

Brutus, who commanded the fleet, and the tribunes and centurions, each of whom had been entrusted with a single ship, did not quite know what to do, or what tactics to adopt. They had ascertained that it was impossible to injure the enemy’s ships by ramming. The turrets were run up; but even then they were overtopped by the foreigners’ lofty sterns, so that from the lower position, it was impossible to throw javelins with effect, while the missiles thrown by the Gauls fell with increased momentum. Our men, however, had a very effective contrivance ready – namely, hooks, sharpened at the ends and fixed to long poles, shaped somewhat like grappling-hooks [as used to pull down town walls]. By means of these the halyards were seized and pulled taut: the galley rowed hard; and the ropes snapped. When they were cut, the yards of course fell down; and as the efficiency of the Gallic ships depended altogether upon their sails and rigging, when they were gone the ships were no longer of any use. Thenceforward the struggle turned upon sheer courage, in which our soldiers easily had the advantage, especially as the fighting went on under the eyes of Caesar and the whole army,[*] so that no act of courage at all remarkable could escape notice; for all the cliffs and high ground which commanded a near view over the sea were occupied by the army.The Gallic War III, 14

Seeing that things were going badly, the Veneti fleet tried to escape, but the weather intervened. The wind suddenly dropped, and the Romans were able to mop-up the becalmed enemy ships. The Veneti were left with no option other than surrender, but Caesar determined to make an example of them:

Accordingly he put to death the entire council, and sold the rest of the population into slavery.The Gallic War III, 16

Translations:

Herodotus Histories by Robin Waterfield

Strabo Geography by Horace Leonard Jones

Pliny the Elder Natural History by H. Rackham

Julius Caesar The Gallic War by T. Rice Holmes

THE PEOPLES OF GAUL

Caesar begins The Gallic War:

Gaul, taken as a whole, is divided into three parts, one of which is inhabited by the Belgae, another by the Aquitani, and a third by a people who call themselves Celts and whom we call Gauls. These peoples differ from one another in language, institutions, and laws. The Gauls are separated from the Aquitani by the river Garonne, from the Belgae by the Marne and the Seine. Of all these peoples the bravest are the Belgae; for they are furthest removed from the civilization and refinement of the Province, traders very rarely visit them with the wares which tend to produce moral enervation, and they are nearest to the Germans, who dwell on the further side of the Rhine, and are constantly at war with them.

“The Province” (hence ‘Provence’) had been a Roman possession since 121 BC.

PLINY THE ELDER, ON GOD AND GODS

… Upheld by the same vapour between earth and heaven, at definite spaces apart, hang the seven stars which owing to their motion we call ‘planets’, although no stars wander less than they do. In the midst of these moves the sun, whose magnitude and power are the greatest, and who is the ruler not only of the seasons and of the lands, but even of the stars themselves and of the heaven. Taking into account all that he effects, we must believe him to be the soul, or more precisely the mind, of the whole world, the supreme ruling principle and divinity of nature. He furnishes the world with light and removes darkness, he obscures and he illumines the rest of the stars, he regulates in accord with nature’s precedent the changes of the seasons and the continuous re-birth of the year, he dissipates the gloom of heaven and even calms the storm-clouds of the mind of man, he lends his light to the rest of the stars also; he is glorious and pre-eminent, all-seeing and even all-hearing – this I observe that Homer the prince of literature held to be true in the case of the sun alone.

For this reason I deem it a mark of human weakness to seek to discover the shape and form of God. Whoever God is — provided there is a God – and in whatever region he is, he consists wholly of sense, sight and hearing, wholly of soul, wholly of mind, wholly of himself. To believe in gods without number, and gods corresponding to men’s vices as well as to their virtues, like the Goddesses of Modesty, Concord, Intelligence, Hope, Honour, Mercy and Faith — or else, as Democritus held, only two, Punishment and Reward, reaches an even greater height of folly. Frail, toiling mortality, remembering its own weakness, has divided such deities into groups, so as to worship in sections, each the deity he is most in need of. Consequently different races have different names for the deities, and we find countless deities in the same races, even those of the lower world being classified into groups, and diseases and also many forms of plague, in our nervous anxiety to get them placated. Because of this there is actually a Temple of Fever consecrated by the nation on the Palatine Hill, and one of Bereavement at the Temple of the Household Deities, and an Altar of Misfortune on the Esquiline. For this reason we can infer a larger population of celestials than of human beings, as individuals also make an equal number of gods on their own, by adopting their own private Junos and Genii; while certain nations have animals, even some loathsome ones, for gods, and many things still more disgraceful to tell of — swearing by rotten articles of food and other things of that sort. To believe even in marriages taking place between gods, without anybody all through the long ages of time being born as a result of them, and that some are always old and grey, others youths and boys, and gods with dusky complexions, winged, lame, born from eggs, living and dying on alternate days — this almost ranks with the mad fancies of children; but it passes all bounds of shamelessness to invent acts of adultery taking place between the gods themselves, followed by altercation and enmity, and the existence of deities of theft and of crime. For mortal to aid mortal — this is god; and this is the road to eternal glory: by this road went our Roman chieftains, by this road now proceeds with heavenward step, escorted by his children, the greatest ruler of all time, His Majesty Vespasian, coming to the succour of an exhausted world. To enrol such men among the deities is the most ancient method of paying them gratitude for their benefactions. In fact the names of the other gods, and also of the stars that I have mentioned above, originated from the services of men: at all events who would not admit that it is the interpretation of men’s characters that prompts them to call each other Jupiter or Mercury or other names, and that originates the nomenclature of heaven? That that supreme being, whate’er it be, pays heed to man’s affairs is a ridiculous notion. Can we believe that it would not be defiled by so gloomy and so multifarious a duty? Can we doubt it? It is scarcely pertinent to determine which is more profitable for the human race, when some men pay no regard to the gods at all and the regard paid by others is of a shameful nature: they serve as the lackeys of foreign ritual, and they carry gods on their fingers; also they pass sentence of punishment upon the monsters they worship, and devise elaborate viands for them; they subject themselves to awful tyrannies, so as to find no repose even in sleep; they do not decide on marriage or having a family or indeed anything else except by the command of sacrifices; others cheat in the very Capitol and swear false oaths by Jupiter who wields the thunder-bolts — and these indeed make a profit out of their crimes, whereas the others are penalized by their religious observances.

Nevertheless mortality has rendered our guesses about God even more obscure by inventing for itself a deity intermediate between these two conceptions. Everywhere in the whole world at every hour by all men’s voices Fortune alone is invoked and named, alone accused, alone impeached, alone pondered, alone applauded, alone rebuked and visited with reproaches; deemed volatile and indeed by most men blind as well, wayward, inconstant, uncertain, fickle in her favours and favouring the unworthy. To her is debited all that is spent and credited all that is received, she alone fills both pages in the whole of mortals’ account; and we are so much at the mercy of chance that Chance herself, by whom God is proved uncertain, takes the place of God. Another set of people banishes fortune also, and attributes events to its star and to the laws of birth, holding that for all men that ever are to be God’s decree has been enacted once for all, while for the rest of time leisure has been vouchsafed to Him. This belief begins to take root, and the learned and unlearned mob alike go marching on towards it at the double: witness the warnings drawn from lightning, the forecasts made by oracles, the prophecies of augurs, and even inconsiderable trifles — a sneeze, a stumble — counted as omens. His late Majesty put abroad a story that on the day on which he was almost overthrown by a mutiny in the army he had put his left boot on the wrong foot. This series of instances entangles unforeseeing mortality, so that among these things but one thing is in the least certain — that nothing certain exists, and that nothing is more pitiable, or more presumptuous, than man! inasmuch as with the rest of living creatures their sole anxiety is for the means of life, in which nature's bounty of itself suffices, the one blessing indeed that is actually preferable to every other being the fact that they do not think about glory, money, ambition, and above all death.

But it agrees with life’s experience to believe that in these matters the gods exercise an interest in human affairs; and that punishment for wickedness, though sometimes tardy, as God is occupied in so vast a mass of things, yet is never frustrated; and that man was not born God’s next of kin for the purpose of approximating to the beasts in vileness. But the chief consolations for nature’s imperfection in the case of man are that not even for God are all things possible — for he cannot, even if he wishes, commit suicide, the supreme boon that he has bestowed on man among all the penalties of life, nor bestow eternity on mortals or recall the deceased, nor cause a man that has lived not to have lived or one that has held high office not to have held it — and that he has no power over what is past save to forget it, and (to link our fellowship with God by means of frivolous arguments as well) that he cannot cause twice ten not to be twenty or do many things on similar lines: which facts unquestionably demonstrate the power of nature, and prove that it is this that we mean by the word ‘God’. It will not have been irrelevant to have diverged to these topics, which have already been widely disseminated because of the unceasing enquiry into the nature of God.Natural History II, 4–5 (Translation by H. Rackham.)

A strigil is a curved blade which was used, after an application of oil, to scrape dirt from the body following bathing or exercise. The, bronze, example pictured is from

A strigil is a curved blade which was used, after an application of oil, to scrape dirt from the body following bathing or exercise. The, bronze, example pictured is from  Perhaps Pytheas was alluding to the sluggish movement of the ‘congealed ocean’ – but there is another possibility. Aristotle (On the Parts of Animals IV, 5) might indicate that a sea-lung is a jellyfish (the name being inspired by the creature’s method of propulsion). As the photo above shows, small chunks of floating ice (called ‘pancake ice’) could well have conjured up that image to Pytheas.

What Aristotle says is: “The ones called ‘holothurians’ and ‘lungs’, as well as other such sea-dwellers, differ slightly from sponges in being detatched; for none of them has perception, and they live as though they were detatched plants.” (Translation by James G. Lennox.)

Perhaps Pytheas was alluding to the sluggish movement of the ‘congealed ocean’ – but there is another possibility. Aristotle (On the Parts of Animals IV, 5) might indicate that a sea-lung is a jellyfish (the name being inspired by the creature’s method of propulsion). As the photo above shows, small chunks of floating ice (called ‘pancake ice’) could well have conjured up that image to Pytheas.

What Aristotle says is: “The ones called ‘holothurians’ and ‘lungs’, as well as other such sea-dwellers, differ slightly from sponges in being detatched; for none of them has perception, and they live as though they were detatched plants.” (Translation by James G. Lennox.)