NEW EMPIRES

Diocletian’s accession, on 20th November 284, is the event which is said to mark the end of a half-century-long period of disruption and distress for the Roman Empire, known as the ‘third-century crisis’, and to usher-in a half-century-long (until the death of Constantine, 22nd May 337) period of recovery and major reform. Indeed, Edward Gibbon, in his influential masterwork, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (published, in six volumes, 1776–88) wrote:

Like Augustus, Diocletian may be considered as the founder of a new empire.Chapter 12

Just a couple of years after his accession, however, Roman Britain broke away from Diocletian and, for a decade, operated as an independent empire.

The death of Carinus, in 285, had left Diocletian as sole ruler of the Roman Empire. Previously, Carinus had ruled in the West, whilst his brother, Numerian (into whose shoes Diocletian stepped), had ruled in the East.[*] Diocletian must have seen the benefit of this division of responsibility, since he quickly raised a trusted younger colleague, Maximian, to the rank of Caesar. Maximian took charge in the West, whilst Diocletian returned to the East. Maximian’s immediate challenge was that:

… in Gaul Helianus and Amandus had stirred up a band of peasants and robbers, whom the inhabitants call Bagaudae, and had ravaged the regions far and wide and were making attempts on very many of the cities … [Maximian] marched into Gaul and in a short time he had pacified the whole country by routing the enemy forces or accepting their surrender. In this war Carausius, a citizen of Menapia, distinguished himself by his clearly remarkable exploits. For this reason and in addition because he was considered an expert pilot (he had earned his living at this job as a young man), he was put in charge of fitting out a fleet and driving out the Germans who were infesting the seas.Aurelius Victor Liber De Caesaribus §39

… Carausius, who, though of very mean birth, had gained extraordinary reputation by a course of active service in war, having received a commission in his post at Bononia [Boulogne], to clear the sea, which the Franks and Saxons infested, along the coast of Belgica and Armorica [i.e. along the northern coast of Gaul] …Eutropius Breviarium Ab Urbe Condita IX, 21

emp200

Many [of the towns] were close to the sea or on navigable rivers. Their improved third-century defences would certainly have made them secure against small Germanic war-bands, and, if provided with flotillas and garrisons, they would have guarded access routes into the hinterland. There is no reason to assume the deployment of regular Roman troops. The municipalities were certainly authorised – and most probably ordered – to construct town-walls. It would be rather surprising if they were not at the same time expected to make some provision for local self-defence, perhaps by creating a militia, perhaps by hiring mercenaries; town-walls mean little without men on the parapets.Further, the construction of a system of coastal forts, known as the ‘Saxon Shore’ forts (of which more later), took place in the late-3rd century. An inscription at Rome (ILS 615) indicates that Diocletian acquired the title Britannicus Maximus before the end of 285. Carinus had previously held the same title, which signals that he, or an officer he delegated with the task, carried out a successful campaign in Britain. Possibly Diocletian simply took over Carinus’ title without having a legitimate claim of his own. Perhaps a campaign initiated by Carinus was brought to a successful conclusion after his death, and so Diocletian claimed the credit. Diocletian apparently dropped the title later, which might suggest that he owed it to a victory achieved by Carausius.Chapter 4 (p.122)

In spring 286 Maximian was elevated to full emperor (i.e. Augustus) status. Diocletian remained the senior partner, however, assuming the title Jovius (after Jupiter), whilst Maximian took that of that of Herculius (after Hercules).

… [Carausius] having captured numbers of the barbarians on several occasions, but having never given back the entire booty to the people of the province or sent it to the emperors, and there being a suspicion, in consequence, that the barbarians were intentionally allowed by him to congregate there, that he might seize them and their booty as they passed, and by that means enrich himself, assumed, on being sentenced by Maximian to be put to death, the imperial purple, and took on him the government of Britain.Eutropius Breviarium Ab Urbe Condita IX, 21

But by this nefarious act of brigandage, first of all the fleet which once guarded the Gauls was abducted by the pirate [Carausius] as he fled, and then in addition a great number of ships were built on the model of ours, a Roman legion was seized, some divisions of foreign troops were intercepted, Gallic merchants were assembled for a levy, considerable forces of barbarians were attracted by means of the booty from the provinces themselves, and all these were trained for naval service under the direction of those responsible for that crime.Panegyrici Latini VIII ‘Panegyric on Constantius Caesar’ §12 (Anon. delivered 297)

emp201

(•)

(•)

EXPECTATE VENI

(Come, awaited one)

with the letters RSR beneath.

Carausius probably had his capital in London, and it is fairly certain that he established a mint there. Some, though by no means all, of his coins bear a mint mark. Those bearing the letter L are considered to have been minted in Londinium (London). Some bear the letter C, but, although there are several candidates – Camulodunum (Colchester), Clausentum (Bitterne, possibly), Calleva Atrebatum (Silchester), Corinium (Cirencester), or, if the C is meant to be a G, Glevum (Gloucester) – their provenance remains unknown. Carausius would appear to have also controlled a portion of northern Gaul, stretching from the coast to, at least, Rotomagus (Rouen), where, probably only early in his reign, he is also believed to have minted coins. Inscriptions on his coinage suggest that Carausius saw himself as a saviour, restoring the traditional values of Rome’s ‘good old days’.

emp202

According to a panegyric (speech of praise) on Maximian, probably delivered on 21st April (Rome’s birthday) 289, since the suppression of the Bagaudae, Maximian had been busy dealing with German invaders:

Scarcely was that unhappy outburst [of the Bagaudae] stilled when immediately all the barbarian peoples threatened the destruction of the whole of Gaul … What god would have brought us such unhoped-for salvation had you [Maximian] not been present?…

I pass over your countless battles and victories all over Gaul. For what speech could do justice to so many great exploits?Panegyrici Latini X ‘Panegyric on Maximian’ §§5–6 (Mamertinus)

Maximian subsequently crossed the Rhine frontier into Germany, eliciting the panegyrist Mamertinus to exclaim:

… all that I see beyond the Rhine is Roman!Panegyrici Latini X ‘Panegyric on Maximian’ §7

At any rate, seemingly by 288 Maximian was in a position to make preparations to cross the Channel and overthrow Carausius. Mamertinus (§12) says that, aided by good weather, Maximian, “throughout almost the whole year”, constructed warships – inland, on rivers, presumably because Carausius was in control of the Channel. It appears that Maximian had defeated Carausius’ forces in northern Gaul, and the assault on Britain was about to be launched, when Mamertinus was speaking.

It is through your good fortune, through you felicity, Emperor, that your soldiers have already reached the Ocean in victory, and that already the receding waves have swallowed up the blood of enemies slain upon that shore.

In what frame of mind is that pirate [Carausius] now, when he can see your armies on the point of penetrating that channel (which has been the only reason his death has been delayed until now) and, forgetting their ships, pursuing the receding sea where it gives way before them? What island more remote, what other Ocean, can he hope for now? By what means can he finally escape the punishment he owes the State unless he is swallowed up by the earth and devoured, or snatched away by some whirlwind onto inaccessible crags?… anyone at all may easily perceive what great success is likely to await you in this maritime venture, considering what a favourable bout of weather has already gratified you.Panegyrici Latini X ‘Panegyric on Maximian’ §§11–12

Great success, however, clearly didn’t await Maximian. A glancing reference in a later panegyric might suggest that the expedition was scotched by “inclemency of the sea”.[*] It is, though, quite possible that Maximian’s forces suffered a defeat at the hands of Carausius – a view which seems to be supported by Eutropius, who reports that:

With Carausius, however, as hostilities were found vain against a man eminently skilled in war, a peace was at last arranged.Breviarium Ab Urbe Condita IX, 22

And Aurelius Victor states that:

… Carausius was allowed to retain his sovereignty over the island, after he had been judged quite competent to command and defend its inhabitants against warlike tribes.Liber De Caesaribus §39

The coin issued by Carausius pictured rightabove shows him alongside Diocletian and Maximian, with the legend CARAVSIVS ET FRATRES SVI, that is ‘Carausius and his Brothers’. On the reverse is PAX AVGGG, which represents ‘the Peace of the three Augusti’.

Carausius may have seen himself as a ‘brother’ to Diocletian and Maximian, but it seems clear that the feeling was not reciprocated. They were simply tolerating Carausius until they were in a position to remove him. In 293, Diocletian inaugurated a system of government known as ‘the tetrarchy’ (rule by four). Each Augustus elevated one of their subordinates to the rank of Caesar – Galerius in the case of Diocletian; Constantius (known as Constantius Chlorus, i.e. ‘the Pale’) in the case of Maximian – and control of the Empire was shared between the four of them. The problem of Carausius became Constantius’ responsibility. He took prompt action:

… you straightway made Gaul yours, Caesar, simply by coming here. Indeed the swiftness with which you anticipated all reports of your accession and arrival caught the forces of that band of pirates who were then so obstinate in their unhappy error, trapped within the walls of Gesoriacum [Boulogne], and denied access to the Ocean which washes the gates of the city to those who had relied for so long upon the sea. In this you displayed your divine forethought, and the outcome matched your design, for you rendered the whole bay of the port, where at fixed intervals the tide ebbs and flows, impassable to ships by driving piles at its entrance and sinking boulders there. You thereby overcame the very nature of the place with remarkable ingenuity, since the sea, moving back and forth in vain, seemed to make sport, as it were, of those to whom escape was denied, and offered as little practical help to those shut in as if it had ceased to ebb at all…

… your divine forethought, Caesar, devised an efficacious plan and did not insult the element [i.e. the sea], so that it did not provoke its hatred but earned its respectful compliance. For what other construction are we to put upon it when immediately necessity and trust in your clemency had put an end to the siege the very first wave which bore down upon those same barriers burst through them, and that whole line of trees, unconquered by the surge as long as there was a need for it, collapsed as if a signal had been given and its guard duty was at an end? The result was that no one could doubt that the harbour, which had been closed to the pirate so he could not bring help to his men, had opened of its own accord to aid our victory. For the whole war could have been finished immediately, invincible Caesar, under the impulse of your courage and good fortune, had not the necessity of the case persuaded you that time should be spent on the building of a navy. During the whole of this period, however, you never ceased to destroy those enemies whom terra firma permitted you to approach …Panegyrici Latini VIII ‘Panegyric on Constantius Caesar’ §§6–7 (Anon. delivered 297)

Whilst Constantius waited until a new fleet was built, Carausius was overthrown and killed.

At the end of seven years [i.e. in 293], Allectus, one of his supporters, put him to death, and held Britain himself for three years subsequently …[*]Eutropius Breviarium Ab Urbe Condita IX, 22

emp203

He [Carausius], in fact, was treacherously overthrown six years later by a man named Allectus …Victor allots Allectus a reign of “a short while”. There is no certainty, but, on balance, it seems likely that Carausius rebelled in the autumn of 286; he was overthrown by Allectus in 293 (Constantius seems to have taken Boulogne pretty quickly after his elevation to Caesar, which was on 1st March 293 – it is widely supposed that his success precipitated the downfall of Carausius); Allectus was overthrown by Constantius (as we shall see) in 296. Victor is the only source who defines the position held by Allectus at the time he rebelled against Carausius. The Latin phraseology Victor uses, though, is open to interpretation, and, encouraged by a longstanding interpretation of the RSR inscription found on some of Carausius’ coins (as on the silver denarius pictured previously), it has been generally supposed that Victor meant that Allectus was Carausius’ finance minister. However, in 1998 Guy de la Bédoyère convincingly demonstrated that RSR is actually a literary allusion, so there is no longer a need to confine Allectus to the finance department.[*] Anthony R. Birley interprets Victor as meaning that Allectus was “in supreme charge by Carausius’ permission”, and suggests he was Carausius’ Praetorian prefect.[*] Anyway, Victor proceeds to claim that Allectus:Liber De Caesaribus §39

… fearing execution because of his misdeeds, had seized power through a criminal act.However, the apparently smooth transfer of power from Carausius to Allectus suggests that the latter had the troops’ backing. Having described the first stages of Carausius’ rebellion (“this nefarious act of brigandage”, above), the anonymous author of the ‘Panegyric on Constantius Caesar’ proceeds to say:Liber De Caesaribus §39

Although your [i.e. Constantius and his ruling partners’] armies were unconquerable in courage, they were novices, however, in the art of seafaring, and we heard that an evil and massive war had grown out of that most miserable act of piracy, although we were confident about its outcome. For, in addition, long impunity for their crime had inflated the audacity of desperate men, so that they gave out that that inclemency of the sea, which had delayed your victory by some necessity of fate, was really terror inspired by themselves, and they believed, not that the war had been interrupted by deliberate policy, but that it had been abandoned out of despair, so much so that now that his fear of a common punishment had been laid to rest one of the henchmen of the archpirate killed him: he judged that after all imperial power was recompense for such a great hazard.The “inclemency of the sea” episode is generally seen as a reference to Maximian’s failed attempt to dislodge Carausius in 289 – either as a genuine reason for the loss of Maximian’s fleet, or as a cover for it being smashed by Carausius’ naval superiority. The panegyrist stresses Britain’s importance to Rome:Panegyrici Latini VIII ‘Panegyric on Constantius Caesar’ §12

… a land so abundant in crops, so rich in the number of its pastures, so overflowing with veins of ore, so lucrative in revenues, so girt with harbours, so vast in circumference.Britain would play a crucial role supplying grain to the Rhine garrisons[*].Panegyrici Latini VIII ‘Panegyric on Constantius Caesar’ §11

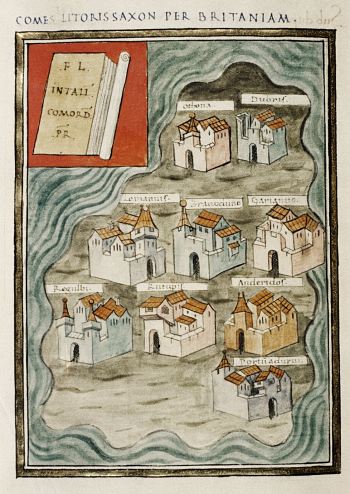

Exactly when in the late-3rd century, and by whom, the decision to establish a coastal defence system in the south-east of Britain – comprising the, so-called, ‘Saxon Shore’ forts – was taken is difficult to determine (a popular theory is that Probus, 276–282, was responsible). What is clear, from numismatic evidence, however, is that, even if it was not initiated by Carausius, both he and Allectus developed the system. The forts get their name from an entry in the Notitia Dignitatum, listing nine forts, identified with sites between the Wash and the Solent, that were under the command of the comes litoris Saxonici (count of the Saxon Shore) about a century after the time of Carausius and Allectus. Perhaps the term ‘Saxon Shore’ was applied because this stretch of coast was vulnerable to raids by the Saxons, but it may be that the Saxons referred to were settlers rather than raiders – by 297, the practice of settling barbarians on land inside the Empire, to provide a ready supply of troops to fight against barbarians outside the Empire, was already established.[*] Whatever the origin of the name, it is, for the most part, accepted that the purpose of this group of forts was to combat sea-borne, Germanic, raiding parties (and presumably, for Carausius and Allectus, an invading Roman force).

emp204

Notitia Dignitatum are usually identified

with the sites shown above.

In 296, whilst Maximian guarded the Rhine frontier,[*] Constantius mounted his assault on Britain. Despite adverse weather conditions, Constantius set sail from Boulogne with a section of his army, whilst the remainder, under his Praetorian prefect Asclepiodotus, sailed from the mouth of the river Seine.[*] Aurelius Victor (Liber De Caesaribus §39) says that Asclepiodotus “was sent ahead with a detachment of the fleet and of the legions”, whereas according to the ‘Panegyric on Constantius Caesar’ (§14), which is of course the contemporary source, it was Constantius who sailed first. Either way, it was Asclepiodotus’ fleet that arrived off the coast of Britain first.[*] Allectus apparently knew of Constantius’ plan, since he had stationed a fleet near the Isle of Wight in order to intercept this section of the invading army, but, as luck would have it, fog enabled Asclepiodotus’ fleet to slip past unnoticed. Having landed on the British coast, Asclepiodotus’ men burned their own ships. Meanwhile, Allectus himself was evidently lying in wait, with a fleet, at another location – presumably one of the Saxon Shore Forts on the Channel coast, east of the Isle of Wight, opposite Boulogne. Constantius had still not arrived, so, leaving his fleet in place, Allectus hastily marched against Asclepiodotus.

Why did the standard-bearer himself of that criminal faction [i.e. Allectus] retreat from the shore that he held? Why did he desert his fleet and harbour, unless it was because he feared you, invincible Caesar, whose approaching sails he had seen, about to arrive at any moment? Whatever the case, he preferred to make trial of your generals than to receive in person the thunderbolt of Your Majesty – madman he, who did not know that wherever he might flee, the power of your divinity would be everywhere that your images, everywhere that your statues, are revered.

He, however, in fleeing you, fell into the hands of your men: vanquished by you, he was crushed by your armies. At last, afraid when he looked back and saw you on his heels, he was stricken out of his senses and rushed to his death so hurriedly that he did not draw up battle line or deploy all the forces which he was dragging behind him, but without a thought for his vast preparations rushed forward with those old chiefs of the conspiracy and divisions of barbarian mercenaries. And furthermore, Caesar, such an asset to the State was your good fortune that almost no Roman died in this victory of the Roman Empire. For, as I hear, none but the scattered corpses of our foulest enemies covered all those fields and hills.Panegyrici Latini VIII ‘Panegyric on Constantius Caesar’ §§15–16

One of the “scattered corpses” was Allectus.

Of his own accord he had discarded the apparel which he had profaned when alive, and he was discovered on the evidence of scarcely a single garment. When death was near, so truly did he foretell what was in store for him that he did not wish his body to be recognized.Panegyrici Latini VIII ‘Panegyric on Constantius Caesar’ §16

Those of Allectus’ Frankish mercenaries who had not been killed in the battle made for London. It would appear that Constantius was still at sea, but some ships that had become separated from his fleet in the fog now arrived in London.[*] Constantius’ soldiers:

… slaughtered indiscriminately all over the city whatever part of that multitude of barbarian hirelings had survived the battle, when they were contemplating taking flight after plundering the city. Your men not only gave safety to your provincials by the slaughter of the enemy, but also the pleasure of the spectacle. O manifold victory of innumerable triumphs, by which the Britains have been recovered, the might of the Franks utterly destroyed, the necessity of submission imposed besides upon the many peoples detected in that criminal conspiracy, by which, finally, the seas were swept clean and restored to everlasting peace! Well may you boast, then, invincible Caesar, that you have discovered another world, you who in restoring naval glory to Roman power have added to the Empire an element greater than all lands.Panegyrici Latini VIII ‘Panegyric on Constantius Caesar’ §17

It was only after the fighting was over that Constantius himself finally arrived on the scene.

(•)

(•)

Whilst troops arrive by ship, a mounted Constantius,

REDDITOR LVCIS AETERNAE

(Restorer of the Eternal Light),

is welcomed by the personification of London, kneeling before her city gates.[*]

And so it was fitting that, as soon as you stepped onto that shore, a long-desired avenger and liberator, a triumphal crowd poured forth to meet Your Majesty, and Britons exultant with joy came forward with their wives and children, venerating not you alone, whom they gazed at as one who had descended from heaven, but even the sails and oars of that ship which had conveyed your divinity, and prepared to feel your weight upon their prostrate bodies as you disembarked. Nor is it any wonder if they were carried away by such joy after so many years of miserable captivity; after the violation of their wives, after the shameful enslavement of their children, they were free at last, at last Romans, at last restored to life by the true light of empire…

… of other areas, some remain which you can acquire if you should wish, or reasons of state require: but beyond the Ocean what was there except Britain? This you have so fully recovered that those peoples, too, who cling to the extremities of the same island, obey your very nod. No reason remains for advancing, unless one were to seek the boundaries of the Ocean itself, which Nature forbids.Panegyrici Latini VIII ‘Panegyric on Constantius Caesar’ §§19–20

Amongst the political, military and economic reforms instigated by Diocletian was the reorganisation of regional government. Provinces were to be reduced in size and increased in number – the military and civil aspects of their administration would be separated.[*] The provinces were to be grouped into territories called dioceses – each diocese would be supervised by an official called a vicarius (from which ‘vicar’). The whole empire was to comprise twelve dioceses – one of them would be Britain. These dramatic changes, which would take a considerable time to work through, began around the time that the tetrarchy was created in 293. In 296, after the overthrow of Allectus, the new order could be introduced in Britain also.

During Caracalla’s reign (211–217), the province of Britannia had been divided into two provinces: Britannia Superior (based on London) and Britannia Inferior (based on York). Under Diocletian’s reformed system, the diocese of the Britains (dioecesis Britanniarum) comprised four provinces: Britannia Prima (based on Cirencester), Britannia Secunda (based on York), Flavia Caesariensis (based on Lincoln), and Maxima Caesariensis (based on London).

emp205