THE ROMAN ARMY IN BRITAIN

Part I

From Claudius’ invasion in AD 43 to Diocletian’s accession in 284.

The army comprised two main sections: the legions and the auxiliary units (auxilia). There were around thirty legions distributed among the Empire’s provinces – the number wasn’t fixed, some legions were lost, others were disbanded or created according to necessity. A legion was divided into ten cohorts, and each cohort was further divided into six centuries. A century was normally made up of eighty men (not a hundred as might be supposed), and each one was divided into ten squads (contubernia) of eight men who would share a tent or barrack-room. It appears, though, that, from round-about 70, the First Cohort was arranged differently, having only five centuries, but of double the size (i.e. one hundred and sixty men). A legion was a heavy-infantry unit, but each had a contingent of one hundred and twenty horsemen who functioned as messengers and scouts.

A legion’s commanding officer, the legate (legatus legionis), was from the top-rung of Roman society – the senatorial class. He was assisted by six military tribunes, the senior of whom (tribunus laticlavius) would be a young man of senatorial rank getting his first taste of military life. The other five (tribuni angusticlavii) were of the, slightly lower status, equestrian class (sometimes called ‘knights’). The legionaries themselves were Roman citizens, recruited from across the Empire. After around fifteen years service, a man might have achieved the rank of centurion. As the name indicates, a centurion was in charge of a century of men, so (on the basis of the First Cohort having five, double-strength, centuries) there were fifty-nine per legion. The senior centurion of the First Cohort, and hence of the whole legion, was the primus pilus (literally, ‘first javelin’), a post which conferred equestrian status on its holder. He might then become camp prefect (praefectus castrorum), making him third in command of the legion (after the two senatorial officers).

Frequently, to avoid removing a whole legion from its post, a detachment – a vexillation (from vexillum, the banner which identified the unit) – would be despatched, possibly with detachments from other legions, to deal with any emergency.

The legions are as renowned for their engineering expertise as they are for their fighting skills. As well as temporary structures built whilst campaigning, they were also responsible for permanent infrastructure projects, such as roads, bridges and fortifications.

A legion (legio) is primarily identified by a number, but, as a result of the somewhat impromptu way legions were created over the years, the number may not be unique – in Britain for instance, there was, for a time, two 2nd Legions. They also have titles, however, and the combination of number and title is exclusive to a particular legion. From the invasion of 43 until about 87 there were normally four legions garrisoned in Britain. Thereafter, until the 4th century, three legions were usually resident. The British legions were:

Legio II Augusta

Probably an already extant 2nd Legion awarded its present title by Augustus (the first emperor, 27 BC–AD 14). The only legion known with certainty to have taken part in the invasion. It seems to have remained in Britain for the duration of Roman occupation.

Legio II Adiutrix Pia Fidelis

Adiutrix means ‘Helper’. Formed, during a civil war, in AD 69 (the Year of the Four Emperors), apparently from marines of the Ravenna fleet, and granted the title Pia Fidelis (‘Loyal and Faithful’) by, the victor, Vespasian. In Britain from 71 (probably) until about 87.

Legio VI Victrix Pia Fidelis

Formed by Octavian (who became Augustus), probably in 41–40 BC. Victrix presumably refers to a victory in Spain, where the legion was posted from 30 BC to AD 69. Pia Fidelis awarded by Domitian in 89. Arrived in Britain in 122 (probably) and still present at the end of the 4th century.

Legio IX Hispana

Origins uncertain, but served in Spain from 30 BC until about 19 BC – hence Hispana. Probably part of the invasion army in AD 43, though its presence in Britain is not confirmed until 60 (see Boudica’s Rebellion). The fate of IX Hispana continues to be the subject of debate – known to be in Britain in 108, but had ceased to exist by c.165.

Legio XIV Gemina Martia Victrix

Origins uncertain. Possibly formed by Octavian in 41–40 BC. Gemina (‘Twin’) suggests that it was amalgamated with another legion after Octavian’s defeat of Mark Antony, at Actium, in 31 BC. Probably part of the invasion army in AD 43, although its presence in Britain is not confirmed until 60. Apparently awarded the title Martia Victrix (‘Martial and Victorious’) – by Nero, who thought the 14th “his best soldiers” (Tacitus Histories II, 11) – for its role in crushing Boudica’s rebellion. Left Britain around 66/67, returned in 69, but left permanently the following year.

Legio XX Valeria Victrix

Formed by Octavian, in 41–40 BC or after the battle of Actium (31 BC). Probably part of the invasion army in AD 43, although its presence in Britain is not confirmed until 60. Probably awarded the title Valeria Victrix (‘Valiant [?] and Victorious’) for its role in crushing Boudica’s rebellion. Last recorded at the end of the 3rd century – may have been disbanded in the 4th century.

The auxilia were non-citizen units raised from the provinces, and sometimes beyond the Empire’s frontiers. Their names reflect the tribe or region where the unit was originally raised. After some time posted ‘abroad’ the unit’s regional identity would become diluted as soldiers were replaced with recruits from elsewhere, but the original regional name was retained. As well as infantry, including specialists that the legions did not possess, such as slingers and archers, the auxilia provided the army’s cavalry.

The infantry was organized into cohorts and the cavalry into wings (alae). Usually the units were, ‘five hundred strong’ (quingenaria), but there were also some units ‘one thousand strong’ (milliaria). A quingenaria infantry cohort was, like a standard legionary cohort, divided into six centuries of eighty men, and this does indeed produce a unit around ‘five hundred strong’. A milliaria infantry cohort, however, had only ten centuries, which falls considerably short of being ‘one thousand strong’. Similarly, a quingenaria cavalry wing comprised sixteen squadrons (turmae) of thirty or thirty-two (it isn’t clear which) troopers, giving a unit size about ‘five hundred strong’, whilst in a milliaria cavalry wing there were only twenty-four squadrons, so it too falls quite a way short of its advertised strength.

There were also auxiliary units where the infantry was supplemented by a small cavalry force: cohortes equitatae. In this case, a quingenaria cohort seems to have comprised the usual six centuries of infantry, but with the addition of four squadrons of cavalry, hence it exceeded its nominal size. A milliaria cohort, seemingly comprising ten centuries of infantry plus eight squadrons of cavalry, was comfortably ‘one thousand strong’. The horsemen of the cohortes equitatae were apparently not as well equipped, nor, indeed, as well paid, as those of the alae.

As in the legions, each auxiliary century had a centurion. The equivalent rank in the cavalry was a decurion, who was in charge of a squadron. After the completion of twenty-five years service, the men were granted, the coveted, Roman citizenship. There are instances of auxiliary units being commanded by tribal chieftains and by legionary centurions, but mostly they were commanded by prefects of equestrian status. The commander of a cavalry wing was a prefect regardless of the unit’s size, but a ‘one thousand strong’ cohort was usually commanded by a tribune – in either case, the cohort commander was outranked by the cavalry prefect.

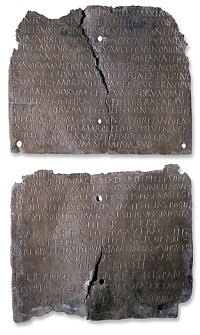

It is evident that more than half of the garrison of Britain was auxiliaries. Auxiliary units are rarely referred to in literary sources, so the evidence for their presence in Britain comes from various types of inscription – including the famous writing tablets from Vindolanda. From the mid-1st century to the beginning of the 3rd century, so-called ‘military diplomas’ – in effect, certificates of citizenship – were given to auxiliary soldiers on their discharge after twenty-five years of service (or sometimes before, in cases of outstanding performance – indeed, it was possible for a whole unit to be rewarded with a grant of citizenship). The diplomas (they actually comprise two engraved bronze plates, wired together), which were copied for the individual retiring soldier from master records kept in Rome, contain a great deal of precise information, for instance:

Photograph courtesy of

the British Museum.

The Emperor Caesar Nerva Traianus Augustus [i.e. Trajan, 98–117], conqueror of Germany, conqueror of Dacia, son of the deified Nerva, Pontifex Maximus, in his 7th year of Tribunician Power, 4 times acclaimed Imperator, 5 times Consul, Father of his Country, has granted to the cavalrymen and infantrymen who are serving in four wings and eleven cohorts called: I Thracum; and I Pannoniorum Tampiana; and Gallorum Sebosiana; and Hispanorum Vettonum, Roman citizens; and I Hispanorum; and I Vangionum, one thousand strong; and I Alpinorum; and I Morinorum; and I Cugernorum; and I Baetasiorum; and I Tungrorum, one thousand strong; and II Thracum; and III Bracaraugustanorum; and III Lingonum; and IIII Delmatarum; and are stationed in Britain under Lucius Neratius Marcellus, who have served twenty-five or more years, whose names are written below, citizenship for themselves, their children and descendants, and the right of legal marriage with the wives they had when citizenship was granted to them, or, if any were unmarried, with those they later marry, but only a single one each.

The 14th day before the Kalends of February, in the consulships of Manius Laberius Maximus and Quintus Glitius Atilius Agricola, both for the 2nd time [i.e. 19th January 103].

To Reburrus, son of Severus, from Spain, decurion of Ala I Pannoniorum Tampiana, commanded by Gaius Valerius Celsus.

Copied and checked from the bronze tablet set up at Rome on the wall behind the temple of the deified Augustus, near [the statue of] Minerva.

[Witnessed by] Quintus Pompeius Homerus; Gaius Papius Eusebes; Titus Flavius Secundus; Publius Caulius Vitalis; Gaius Vettienus Modestus; Publius Atinius Hedonicus; Tiberius Claudius Menander.RIB (Roman Inscriptions of Britain) 2401.1

The above diploma was found near Malpas, Cheshire. Evidently its recipient, the Spanish decurion Reburrus, settled in Britain after his discharge from the army. Others, though, chose to return home. One such was Gemellus, son of Breucus, who was discharged on 17th July 122. It just so happens that Gemellus had served in the same unit as Reburrus – Ala I Pannoniorum Tampiana (Tampiana probably from Lucius Tampius Flavianus, who was governor of Pannonia in 69) – though, of course, nineteen years later. Unlike Reburrus, though, Gemellus actually was from Pannonia. His diploma was found at Brigetio in Pannonia Superior (now Szőny, Komárom, Hungary), and it names fifty units – thirteen cavalry wings and thirty-seven cohorts – that had men receiving citizenship in Britain on the same date.

There was, in fact, no ban on citizens joining the auxiliaries, and, as time progressed and the number of citizens grew, that particular distinction between legions and auxiliary units faded. It disappeared completely when, in 212, by what is known as the Constitutio Antoniniana, Caracalla conferred Roman citizenship on all of the Empire’s free people.

Caracalla’s father, Septimius Severus, had, in the mid-190s, created three new legions. Each had an equestrian, rather than a senatorial commander. In the 260s, Gallienus excluded men of senatorial rank from military command.

The Empire’s frontiers came under unprecedented pressure during what is known as the Third-Century Crisis of 235–284. In order to increase the army’s ability to mount a rapid response over a wide area, greater emphasis was placed on the cavalry, and splitting legions into vexillations became the norm.

Part II

From Diocletian’s accession, in 284, onwards.

The structure of the Late Roman army was the result of reforms instituted by Constantine (306–337), which built on the reforms of Diocletian (284–305), which, in turn, built on lessons learned during the Third-Century Crisis. The upshot of this evolutionary process was that the army was divided into two main elements: the comitatenses (mobile field-army) and the limitanei (permanent frontier-troops). (The term limitanei is first attested in 363: Theodosian Code XII, 1.56.) The commander of the limitanei in a particular region, which could range over more than a single province, had the title dux (duke) or sometimes, rather grander, comes (count). When a detachment of the comitatenses was assembled for a particular mission, it would be commanded by a comes.

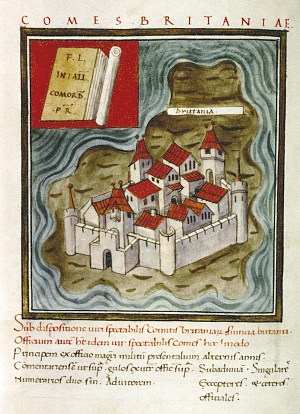

In the Notitia Dignitatum (Register of Dignitaries) – a list of Roman civil and military posts, compiled round-about 400 (its precise date and purpose are subjects of much debate) – the limitanei of Britain are under the command of two officers: the dux Britanniarum (duke of the Britains) and the comes litoris Saxonici (count of the Saxon Shore).

Under the dux Britanniarum are listed thirty-seven units – dotted about what is now northern England, and on Hadrian’s Wall. The bases of the first fourteen units – appearing before those categorized as “along the line of the wall” – feature in an illustration representing the duke’s command (rightabove). The list begins with the Sixth Legion, commanded by a prefect. Its base is not actually named by the Notitia, but presumably it was York, which had been HQ of the the Sixth (i.e. Legio VI Victrix) since c.122. The dux Britanniarum himself was probably also based at York. (Under the heading “along the line of the wall”, are listed units occupying forts along Hadrian’s Wall – from east to west, and including Vindolanda – but then, without a further heading, are another seven units which are all evidently in the wider north-west of England. Not all the forts in the duke’s command are certainly identified.)

The comes litoris Saxonici has command over nine forts – ranged round the south-east coastline, and known as Saxon Shore forts. Why this particular officer had the elevated title of comes is not obvious – perhaps the command originally included the Gallic as well as the British side of the Channel. The unit occupying the fort at Richborough is named as the Second Augusta Legion, commanded by a prefect. Richborough is only a fraction of the size of II Augusta’s erstwhile fortress at Caerleon, so the new unit was clearly much smaller than the old legion.

The third of the old British legions, Legio XX Valeria Victrix, does not appear in the Notitia. It is last attested on coins issued by the usurper Carausius (286–293, see New Empires), and it may well have been disbanded and dispersed into other units in the intervening period. The legion’s old fortress, at Chester, does not appear either. Neither does that of II Augusta, at Caerleon, in modern South Wales. In fact, the area that is now Wales does not figure in the Notitia at all. The usurper Magnus Maximus (383–388) is particularly associated with Wales – being absorbed into Welsh folklore as Macsen Wledig – and he is said (Gildas De Excidio Britanniae §13) to have withdrawn large numbers of troops from Britain, who “never returned” (see Ruin).

The Notitia places a force of the comitatenses, a small field-army, in Britain. The nine units listed – three infantry, six cavalry – are commanded by the comes Britanniarum (count of the Britains). The name of one of the infantry units, the Secundani Iuniores, might suggest it had been created from a detachment of the old 2nd Legion (II Augusta).

It seems that, when they weren’t actually in the field campaigning, the comitatenses were usually billeted in towns, rather than being stationed in forts.

There was evidently no comes Britanniarum, nor any comitatenses in Britain, in 367/8, at which time the comes Theodosius brought field-army units over from the Continent to restore order after the frontier forces in Britain had been overwhelmed (see A Barbarian Conspiracy). It is widely suggested that the small field-army the Notitia places under the command of the comes Britanniarum was stationed in Britain by Stilicho, in the late-390s.